Ihei Kimura - The Lens that Rewrote Realism in Japanese Photography

Female farmer in Akita, 1953│via Wikimedia Commons│© Ihei Kimura

Imagine Tokyo in the early 20th century. A pre-war city thriving on modernity, while keeping tradition in high regards. In these blooming streets of Shitaya-ku, Ihei Kimura began his journey. Born in 1901, Kimura and his camera would grow to revolutionize the way we see the world.

His relationship with photography started humbly. As a young man in Taiwan, working for a sugar wholesaler, he picked up a box camera. What began as a hobby quickly became an obsession. By 1924, Kimura was back in Tokyo, running his own studio in Nippori, where his lens began to find its voice.

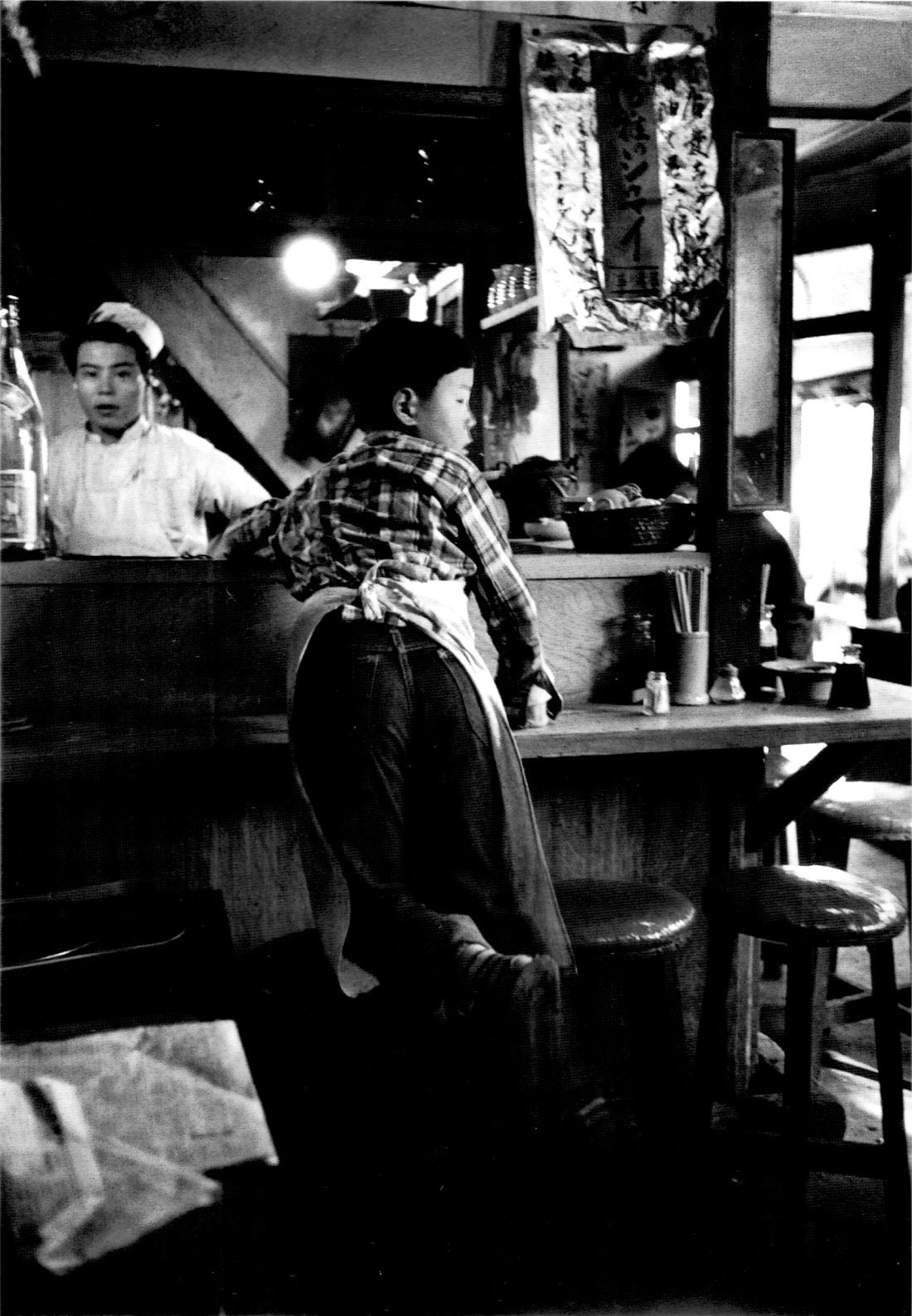

It wasn’t until the 1930s, with a compact Leica 35mm camera in hand, that Kimura’s vision truly took flight. While many photographers of his time leaned into stylized, almost painterly images, Kimura saw beauty in spontaneity. His Leica allowed him to capture life as it unfolded in front of him. The raw energy of Tokyo’s streets and the unvarnished rhythm of daily life. This commitment to realism put him at odds with the pictorialist trends dominating pre-war Japan, but it also made him a pioneer.

Alongside contemporaries like Yonosuke Natori, Kimura co-founded Nippon Kobo in 1933, a collective dedicated to the unembellished portrayal of life. Though short-lived, this group cemented his status as a trailblazer. It was here that Kimura developed what might be called his signature: “snapshot spontaneity.”

A Leica in One Hand, a World at War in the Other

Kimura’s career, like so many of his generation, was shaped by the upheavals of World War II. Stationed in Manchuria, he worked on propaganda publications, a chapter of his life that, while contentious, showcased his ability to adapt his craft to the moment.

Post-war, Kimura turned his attention back to what he loved most: documenting the quiet beauty of ordinary life.

In 1950, Kimura became chairman of the Japan Professional Photographers Society (JPS). Together with Ken Domon, he encouraged amateur photographers to embrace the raw, documentary style he championed. His influence rippled through Japan’s photographic community, planting the seeds for a new era of visual storytelling.

A Parisian Palette and Akita’s Soul

The 1950s also saw Kimura stepping onto the global stage. Trips to Europe, particularly Paris, allowed him to experiment with color photography, years ahead of its widespread acceptance. His series “Pari,” though published posthumously in 1974, stands as proof to his forward-thinking artistry.

Back in Japan, Kimura turned his lens to the rural landscapes of Akita Prefecture. His photographs of Akita villages are a love letter to the simplicity of rural life, capturing the textures of earth, sky, and humans with a reverence that only Kimura could muster.

His portraits deserve their own mention. Whether capturing the contemplative faces of writers or the unguarded expressions of strangers on the street, Kimura’s ability to find the humanity in his subjects remains unparalleled. It’s no wonder he was often compared to Henri Cartier-Bresson, earning him the nickname the Japanese Bresson.

Ihei Kimura passed away in 1974, but his legacy endures. The Kimura Ihei Award, established in his honor, continues to celebrate emerging photographers who push the boundaries of the medium.

Kimura once said that the camera allows us to “grasp the world as it is.” And grasp it he did.

Explore Yukio Mishima's existential journey through captivating novels and controversies.