Japan and West Asia - Bridging Cultures Through Textiles and Calligraphy

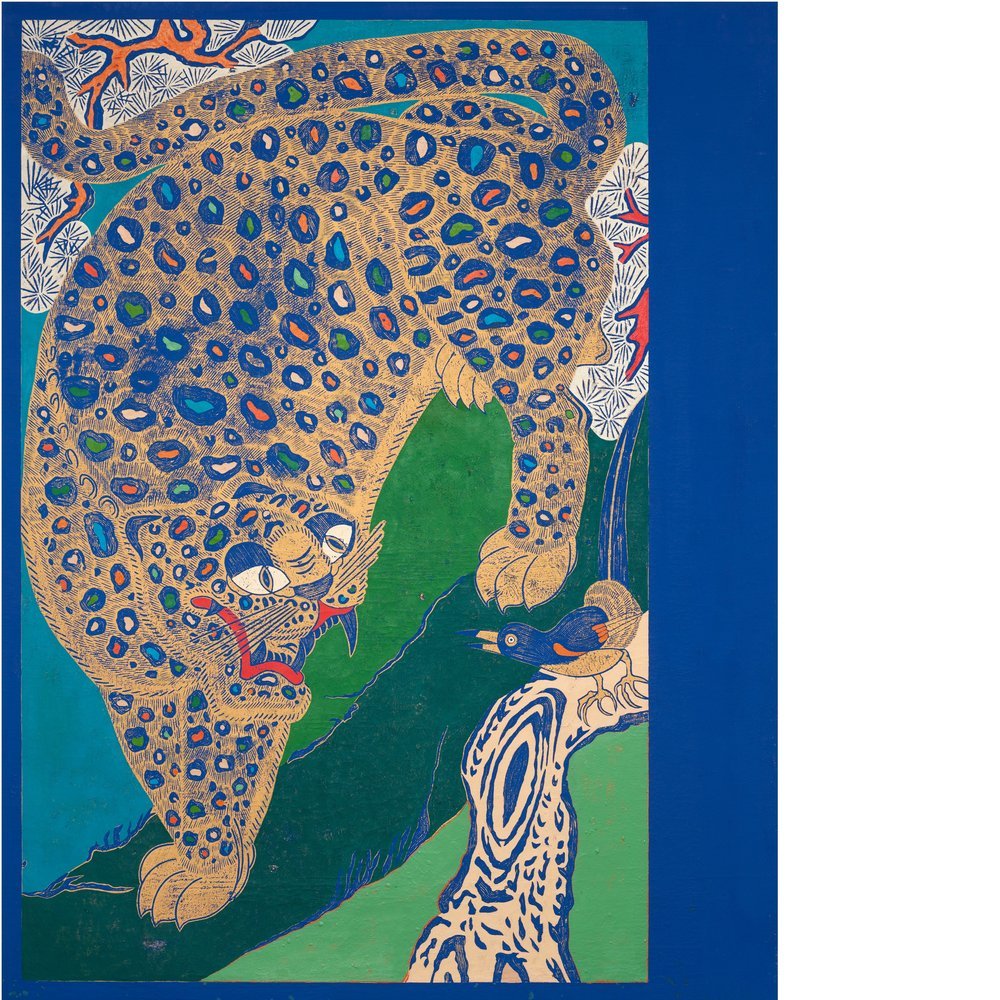

Peacock Tiger│© Kour Pour

There is a longstanding fluidity in art traditions across Asia, dating back to their connection through the silk roads. The silk roads spanned from the Mediterranean Constantinople (modern day Türkiye) to as far as China, acting as the main trade route for goods as well as the cultural ideologies and values that followed.

These transmigratory experiences are reflected in the art of the period which manifests into the modern world, seeing artists like Kour Pour and Aslihan Ciftgul exploring cross-cultural connections. Japanese calligraphy artists like Noaki Yamamoto and Fuad Honda are gaining focus as they present this expression of unity between Arabic and Japanese aesthetics.

apan’s connection with West Asian art (specifically Türkiye, Iran and the wider Islamic world) inspires a hopeful contemplation on art’s ability to connect us globally. In the modern world where many of us find ourselves between harsh border lines, it is important to remember the potential in cultural synergy.

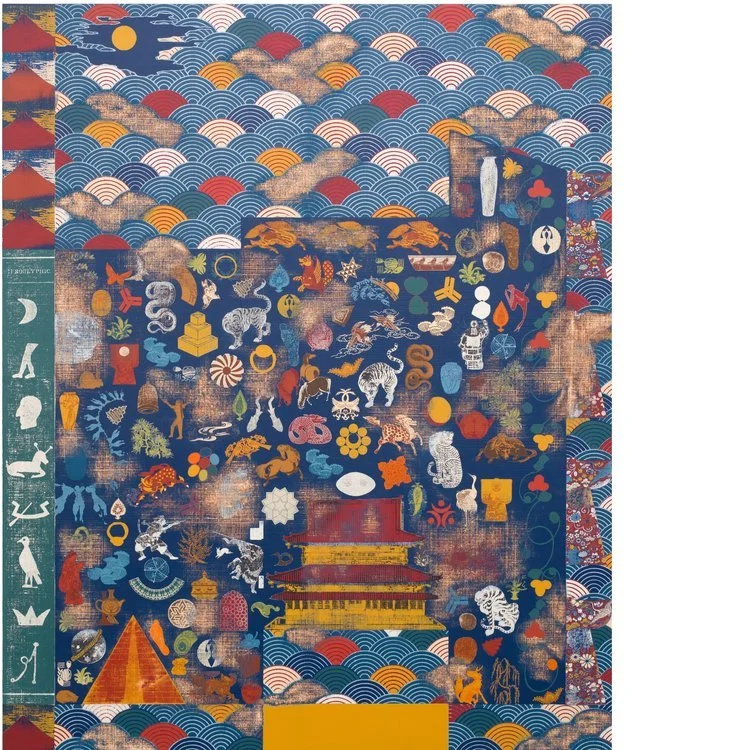

Kour Pour is an Iranian British artist who creates captivating pieces that draw together motifs across cultures, illustrating his own connection to diverse backgrounds. His work mirrors the historical interchange of arts, as he notes in conversation that his international identity allows him to connect artistic spheres because “when you exist between cultures you have the ability to see multiple perspectives.”

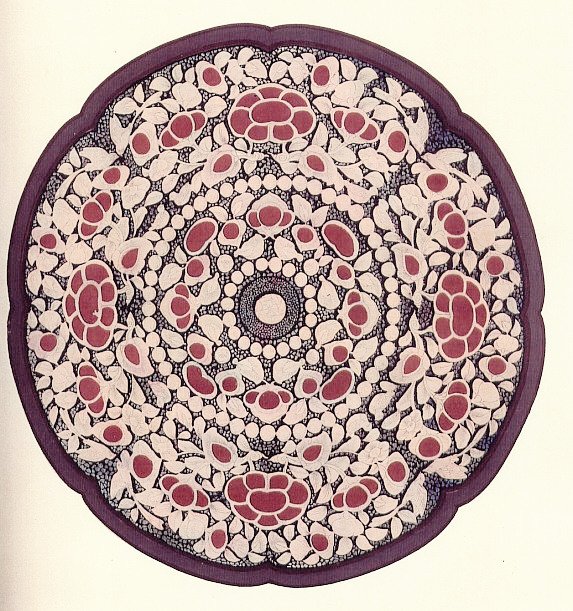

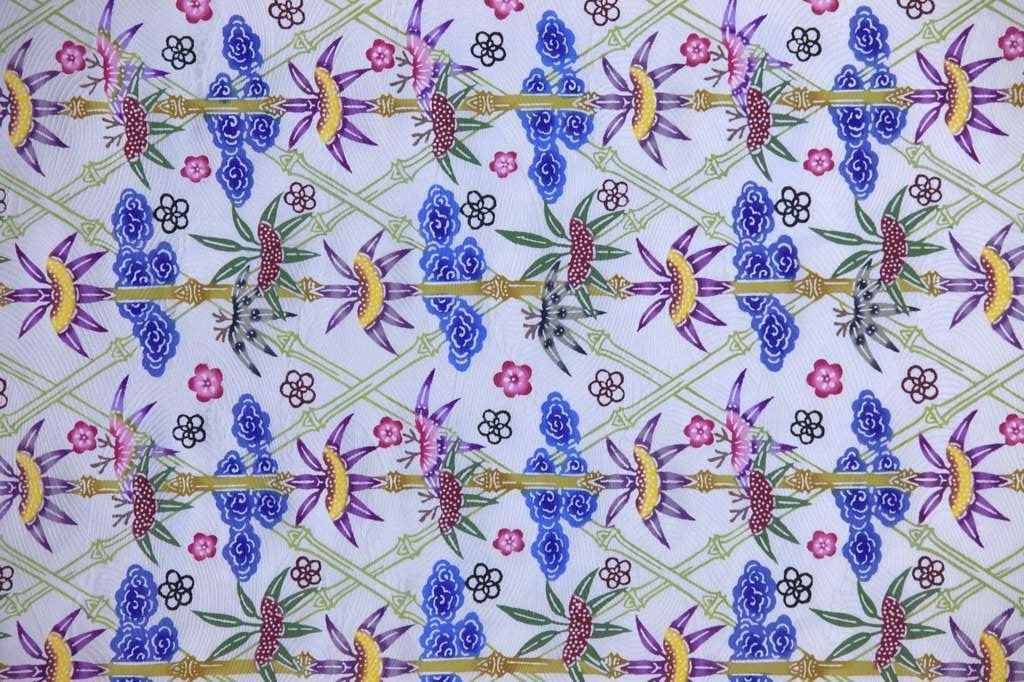

An example of this visual cohesion between Japanese and West Asian art can be found in its textiles: Persian rugs and Japanese Kimonos. Both find their roots in storytelling and symbolising status, weaving intricate patterns that mesmerize. Japanese and Persian (now Iranian) motifs centre around loving attitudes towards people and environment, using detailed embroidery to encapsulate the beauty in the simultaneously simple and complex everyday nature of our lives. The Japanese would have been introduced to Persian arts through meetings as early as the 8th century, with craftsmen and musicians admiring the other’s craftsmanship - relics of the period encapsulate the flow of design between the two cultures.

It is well explored that culture shapes design, with regional heritage being honoured in the artistry that is passed through generations. With globalisation enriching modern design, the cultural context in which art operates becomes a mosaic of the interconnected landscape of the earth, reflecting Asia’s transatlantic systems. Kour Pour articulates that through the everyday presence of textiles, cultures are able to honour and “hold deep love for our personal histories which shape the spaces and cultures we find ourselves in.”

Japanese Kimonos differ in technique and design across regions, with differing dyeing and weaving methods demonstrating generations of devoted craftsmanship. For example, Okinawa's Bingata (a traditional stencil and dying technique) features vibrant, tropical stencil-dyed designs that encapsulate the island's climate: it sees bold patterns of local flora, fauna, and Ryukyuan cultural motifs. In itself, this style blends influences from China and Southeast Asia as the Island was a key trade link. Amongst the distinctive indigo, safflower and other tropical plants expanded the dye palette which were introduced through trade. Its dyeing and layering of bold colors showcase its fusion of Southeast Asian batik.

Similarly, in Persian rug design, the ability of the textile worker is woven into their art as they incorporate their own variety of style and unique design geometry. Individual weavers often incorporated their own personalised flair into creation that pays recognition to the craftmanship of the individual.

It is clear to see that the design captures the artistic beauty of the natural world with a focus on flowers as a primary source for inspiration. The peony flower, known as ‘the king of hundreds of flowers’ which symbolises “happiness”, “richness” and the “noble” are the large, beautiful flowers that bloom from small round buds. They are often coupled with butterflies (a symbol of longevity), popularised from Chinese paintings. The plum blossoms 梅 (Ume) are flowers that live through harsh winters, persisting and blooming late spring so represent “patience” and “beauty”.

We can see that the imagery on the kimono draws from landscape, yet their significance extends beyond aesthetic value; the symbolism gains spiritual significance such that the garment becomes intentional. Similarly, Persian rug design explores the depth of nature in its imagery, seeing the feature of peonies conveying a sense of power, rank and wealth - such motifs are commonly found in city carpets as a symbol of the status of the empire. Another distinctive feature is the Lotus which embodies rebirth, persistence and the beauty of renewal, seeing more connected across design and influence.

In both Kimonos and Rugs, flowers are connected in complex arabesque forms through vines and leaves amongst other, smaller motifs, speaking to nature’s continuous presence in our lives, shaping and forming us alongside the seasons themselves. The textiles reflect our desires for beauty and the persistence of strength; an idea that lies at the heart of both middle eastern and Japanese philosophies.

Moreover, the use of space and geometry is crucial to the mediums, whereby the images carefully balance and work in a dance around each other. The placement is handled with precision and care, presenting a sense of harmony to the textile that recalls the expertise that lies in their design and construction. Both textiles can often seem monochrome yet at a deeper inspection, expand and evolve into their intricate patterns. The notion of the aesthetic appeal of nature seems to connect us globally, seeing an appreciation of beauty as a global source of comfort and inspiration.

Kour reflects the elegance of what is universal in his work, which blends Japanese techniques like Ukiyo-E (woodblock prints) alongside tying influences from his Iranian heritage. His collection ‘Tiger Paintings’ depict tigers from Korean, Chinese and Japanese ink paintings, but tigers themselves are also drawn into Iranian miniature paintings through its interactions with Mughal art, where depictions of tigers were more prominent due to India’s fauna. Through his intricate lacing of cultural dynamics, his work captures his idea that “despite our cultural ‘differences’, we all share the same earth and human experience and are therefore all ultimately connected.”

For Kour, art is “a language of visual communication” that bridges the interior and exterior worlds. For him, art becomes a manifestation of these nuanced experiences of growing up in many different places. It seems that in the way that textiles reflect local origin, so does modern art reflect modern globalisation. Within our current artistic landscape, Kour challenges the rigid ideas of cultural origin, as he believes that “identity which has become too solidified and we must dispel the idea that there is a singular origin of one place/ person or artist.”

Similarly, Japanese and Arabic calligraphy sees cultural boundaries dissolving into a shared artistic language. Just like textiles, calligraphy works to express spiritual contemplation and beauty through notions of rhythm and balance, mirroring their textile counterparts. Calligraphy is a distinct feature of both Arabic and Japanese traditional aesthetic mediums. With language having the power that it does, calligraphy works to make this power visual, encapsulating the beauty of the written word. Japanese calligraphy (Shodo) is derived from Chinese influences and Zen Buddhism, focusing on harmony and a ‘capturing of the writer's spirit’. Similarly, Arabic calligraphy highlights the spiritual and the sacred, aiming to transcribe the Qur’an with honour and dignity. Both are artistic, meditative processes that embody rhythm and flow through fluid sweeping motions, just like the weaving work of fabric and rug construction.

Both systems also centre around the concept of balance. Black ink creates negative space (known as ‘Ma’ in Japanese calligraphy) enhancing cursive design and allowing for contemplation on silence as there is room for the empty space to ‘speak’. In Zen philosophy, Ma represents the idea that emptiness is not void but full of potential. In Arabic calligraphy, the unmarked area around text reflects the depth of meaning of the ineffable and what exists beyond the visual eye. Both are rooted in their spiritual surroundings and are therefore aligned in both composition and deeper significance, much like the textile artform. The interplay of presence (ink) and absence (space) resonates with the philosophies of the cultures, highlighting the connections of intention and artistic technique.

With artists like Dr. Naoki Yamamoto (@japaneseislamicateart on instagram) unifying the forms through artistic means, it is clear that the cultural interaction of these worlds is gaining focus. The Japan Arabic Calligraphy Association promotes this intricate art form through over 20 classrooms nationwide with Japanese participants gaining international acclaim, winning multiple awards at the prestigious International Calligraphy Competition in Istanbul.

Fuad Honda Koucichi is Japanese Arabic calligrapher who worked alongside the Turkish calligrapher Hasan Çelebi, then going on to win awards for his work on Islamic art. He aims to “process the beauty of the calligraphy through my own internal cycle, reconstruct it, and share the results”. He notes that the “keen eye for beauty of the Japanese enables them to re-envision the splendid art of the Arab world” and that Japanese “understand and empathize with the thirst for natural beauty so keenly felt by the people of the Middle East”, through this “shared aesthetic sense”, he hopes to work together to deepen cross-cultural communication.

This respect and longing for the unity of traditional arts is echoed by Turkish artist Aslıhan Çiftgul, who has close ties to the Japanese art scene. She observes that “the common denominator of all kinds of traditional Japanese arts/craft with traditional Turkish arts/craft is ‘patience’”. She stresses that both cultures' work “are incredibly detailed and require mastery” placing honour on Japanese art in particular which she sees as “a discipline that requires talent, an intensive training process from apprenticeship to mastery, years of dedication, and intelligence.”

Çiftgul’s own ‘Miracle’ exhibition reached Japan in her first personal exhibition in Tokyo. She claims the exhibition was a kind of ‘miracle’ in itself, seeing it displayed alongside valuable works of art by Japanese and Turkish artists, “brought together under one roof of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art”. The piece itself reflects the desire for harmony across cultural barriers and differences, where the collective can gather “in a sacred space to become one body.” Çiftgul illustrates herself at the center, embodying “anyone, the self, the human being” contemplating on whether the justice and peace she desires can manifest through the individual.

In conversation with Aslıhan, she beautifully articulates the essence of intercultural artistic practices. She states at the exhibition, “we all experienced the unifying power of art, its spine-chilling effect and the incredibly honorable happiness. I believe that one of the best tools to develop friendship and love between people across borders will be artistic activities and organizations that will bring them together, produce together, get to know each other and share. Art projects create opportunities for people to collaborate.

In this way, people from different cultures can find their common and different points, experience the excitement and enthusiasm of sharing them with each other, and they unite by carrying out joint projects together. They create unforgettable moments and memories that will last a lifetime. My motto that I always repeat is: ‘Art Unites’. We should not forget that, without a doubt, despite all our differences, it is possible to love each other. Because we have very important and valid values to build a peaceful and fraternal life.

In summary, the interaction between Japanese and West Asian art, seen in textiles, calligraphy, and modern art, highlights connections between cultures that transcend borders. Artists like Kour Pour, Aslıhan Çiftgul, Dr. Naoki Yamamoto and Fuad Honda Kouichi demonstrate how shared appreciation for aesthetics and craftsmanship have the ability to unite differing traditions. This cultural synthesis allows for a deeper understanding of our shared human experience, particularly with the works themselves being built on principles of balance and harmony, thus highlighting art as a necessary means to support awareness, collaboration and compassion in cross-cultural communication.

Billboards reimagined as Shibuya’s streets become Tokyo’s art gallery.