The Radio Pirates of Tokyo

© Toshiyuki Maeda

Pirate radio was once the primary area of counterculture, contributing to the growth of rock, hip hop, afrobeat, and even mainstream culture and politics. In the 1980s, Japan experienced a massive, or as it is sometimes called, a “micro” pirate radio movement. Countless radio stations that could only broadcast within walking distance appeared; they were deeply experimental, doing things like hanging microphones from the ceiling or making portable radio stations by putting their equipment on bicycles. Many of them even attempted to turn listeners into active participants and would let anyone broadcast on the show. This mini-FM movement was pivotal to radio culture in Japan and has never been thoroughly explored.

What Is Pirate Radio?

Pirate radio is an illegal form of communication through unlicensed radio broadcasts. In the 40s, it was standard for pirate radio stations to be held on the docks of ships, with the names of the radio stations being the names of the vessels where they were located. Radio Caroline, Radio Veronica, Wonderful Radio London, and others across Europe were boundary-pushing, being pivotal to the growth of rock, afrobeat, and dancehall music. The DJs were willing to give up anything, even going so far as having disputes with the Navy (and in some cases, armed disputes with each other), since radio was initially held in international waters.

In practically every country where it was established, independent radio was directly opposed by law. The United Kingdom saw police raids, arrests, and in one instance, even the use of explosives in order to force entry into Interference FM’s apartment building. This often resulted in a game of cat and mouse, with the radio hosts having multiple locations and lookouts in the event the police came. The police, on the other hand, were pushed to shut down radio stations because they were seen as dangerous and as “corrupting the youth”, similar to contemporary complaints about anime and video games.

The cultural significance of pirate radio is hard to imagine because radio is no longer a primary medium of communication; it has been supplanted by the internet, streaming services, podcasts, social media, and so on. However, from the 60s to the 80s, none of this existed, and radio was a standard means of entertainment; everyone had a Walkman and cassette tapes, everyone played radio music in their cars, and it was common for children to gather to listen to “radio shows” every night.

However, the primacy of radio is precisely what led to its regulation by the government; especially given that radio technology itself truly came about during World War I, many countries were concerned that it could be used to leak information that would give opposing countries advantages in war. Initially, radio was only allowed to be used by government institutions and was usually regulated to things like communication between ships or emergency broadcasts. When radio became a form of entertainment, it was still under heavy government regulation, and in most countries, there were only a handful of licensed radio shows.

This control is what led to the rise of pirate radio in the first place. People felt that the music broadcasted on public stations was not varied enough, and as different communities emigrated to cities like London and Paris, they felt that the radio did not accurately represent them (one could compare this to the debates around representation in movies today). Some decided to take matters into their own hands and made their own stations.

Radio Home Run│© Toshiyuki Maeda

Pirate Radio in Japan

Japan, for its part, has its own history with pirate radio but with aspects that are unique to the country’s geography and laws. Radio faced heavy regulations in Japan from the early 1900s, such as the 1915 Radio Telegraph Law that put radio under the exclusive control of the Japanese Ministry of Communications. Regulations continued for decades, and by the 80s, most cities in Japan only had one officially licensed station, usually run by a retired government official.

There have been documented pirate radio attempts in Japan since the 50s. The most notable instance of pirate radio is the case of FM Koenji due to its popularity and police suppression, but many magazines and articles also document radio enthusiasts experimenting with toy transmitters made for children (for example, one Popeye article from 1972 talks about “interesting ways to use a micro transmitter”). This is due to the Radio Regulations Law, which explicitly stated that “extremely weak radio waves” did not need to be licensed. This legal loophole is what led to the rise of a new pirate radio movement in 1980.

The “Mini-FM” movement spread all over the country though its primary base was Tokyo. Sources vary on the number of radio stations that appeared at the time, with estimates ranging from around 160 to over a thousand. This pirate radio movement was defined by having radio stations that only worked within walking distance; Tokyo’s population density meant that even in a small area, it was still possible to gain a few thousand listeners (one only needs to think of a place like Shibuya crossing in order to understand how pirate radio worked in Japan).

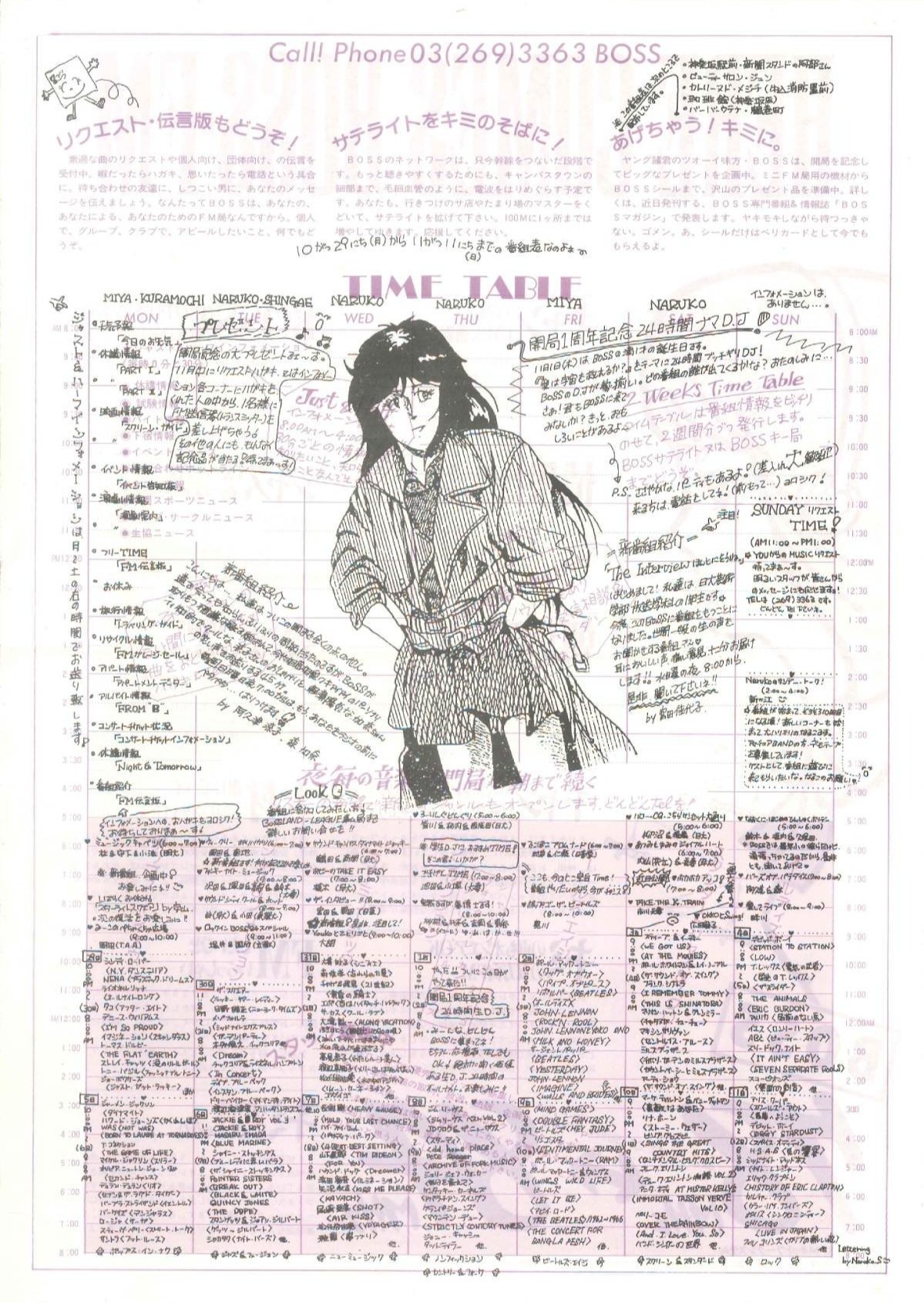

The radio stations themselves had a certain “local” and “DIY” aesthetic, with the use of self-published papers, stylized verification cards, and some even experimented with “cassette magazines”, mass-produced cassette recordings that they would leave on top of trash cans, in bathroom stalls, and anywhere else they could easily be found.

They often attempted to turn listeners into active participants; for example, the college radio station BOSS-FM held “radio workshops”, and a couple of stations held contests to give away equipment. There is barely any documentation about this movement in English, and even in Japanese, the sources are scant. There is no comprehensive documentation on the mini-FM in either Japanese or English. This will be the first attempt to change that.

Mini-FM Stations

Generally speaking, the first “mini-FM” station recognized as such is KIDS. KIDS was a radio station started in 1982 by Yoshimi Ueno, a successful musician by any measurement, creating numerous successful bands and being the one responsible for the first use of the “stage truck” in 1976, a staple of Japanese performance culture (the stage truck market is estimated to be worth $3.47 million by 2033). Yoshimi was inspired after hearing the Hawaiian radio station KIKI FM; KIDS had a tropical aesthetic, with bands such as Coconut Boys, Pineapple Boys, and Orange Sisters. The bands’ album covers often had palm trees and were set on beaches (look at Coconut Boys’ debut album Mild Weekend which is a colored pencil drawing of a Hawaiian beach), and the sound of each band was influenced heavily by American surf rock.

KIDS was massively successful, often selling out their releases within a single day. The Pineapple Boys album Fabulous even became a movie soundtrack. In some sense, KIDS was the closest thing Japan had to a “commercial” radio station similar to the likes seen in America around the same time. Each radio broadcaster had a bubbling personality, and they often used English nicknames, such as “Candy”, “Sandy”, etc. to give a sense of “cuteness” to the broadcast and attract listeners.

The radio station received much media coverage, and many similar stations popped up in the 1980s. Furthermore, notable city pop artists (the most popular form of Japanese music at the time), such as Eiichi Ohtaki and Tatsuro Yamashita, were directly involved with the station. It is interesting to note that Tatsuro Yamashita’s Come Along is framed as being a KIKI broadcast (before each song, there is an American narrator who says, “You’re listening to KIKI”), the exact same station that inspired KIDS.

Though no station became as popular as KIDS, plenty of smaller stations followed suit. Many ran in places like college campuses and coffee shops. For example, in Daikanyama, there was a radio station called Two & A Half that played soul and jazz fusion. Many of these stations ran in the night, starting around 9 PM, and lasting into the early hours of the morning. These radio stations often held events, contests, giveaways, and in one case of IBS-FM, a radio station in Osaka, there was even a community BBQ.

These radio stations aspired to be like American broadcasts (more or less, the only country where commercial radio stations were widely allowed). The DJs aspired to be personalities, and many listeners tuned in just as much for the broadcaster as they did for the music. Some anonymous listeners in Osaka even reported taking notes on the broadcasters’ life events, their likes and dislikes, and so on. However, there was another “section” of the mini-FM movement that focused on radio technology as a means of communication. They made various talk shows and sought to use pirate radio to create new communities.

This “section” of pirate radio was led by media critic and artist Tetsuo Kogawa. In 1983, he started his station Radio Home Run. It had started in an embryonic form one year prior as Radio Polybucket at Wako University. The name was a reference to “polyethylene” trash bags, and in Kogawa’s own words, “the name derived from their wish to be as a trash can in which many unknown, worthless or lucky-finds, anyway-reusable things are filled”.

Tetsuo Kogawa for RHR│© Toshiyuki Maeda

Kogawa started by broadcasting university seminars on the station; at the time, there were attempts to “open” the university as an institution (especially in connection to the left-wing Zenkyoto movement of the time), and there were even books like the “Manual for Fake Students (ニセ学生マニュアル)” that gave explicit instructions on how to enter university lectures without identification. Of course, many professors did not agree with this, but Kogawa stated that he did not mind and estimated that around 50% of attendants at his lectures were not students of the university.

Some self-published magazines from Suigyu Gakudan, a band closely connected to the mini-FM scene, show the extent to which Radio Polybucket attempted to experiment and turn listeners into active participants. For example, an article from 1983 states that Kogawa thought about holding the station outside in an abandoned car so that those passing by could participate. This idea would be seen a few years later when Radio Home Run, the evolved form of the station, took its equipment on a bicycle and broadcasted all around Tokyo (similar ideas at the time, such as the “radio taxi”, can be seen from other stations).

Radio Home Run started in Shimokitazawa, a neighborhood in central Tokyo, in 1983. It was an active attempt to create community by having anyone able to become part of the show. Giving the station’s telephone number and address after the end of each show was standard practice, which inspired curious listeners to get involved. There are recordings of Radio Home Run broadcasts on Kogawa’s website; they show a variety of shows, from music to talk shows, and the station even held some interviews with notable figures such as the French philosopher Felix Guattari (whose philosophy inspired the creation of the station in the first place) the Canadian artist-curator Hank Bull, and even the famous media activist Dee Dee Halleck.

Kogawa criticized the KIDS-style radio stations, as he saw them as not truly understanding the potential of mini-FM. For him, the stations had to be small because that was the only way they could truly foster communities. In connection to this, it’s interesting to note that a research paper by Takashi Wada found that many mini-FM stations in Osaka fell precisely when they gained popularity because they could not keep up with demand and keep the original nature of the radio station as they grew.

Tetsuo Kogawa was, by far, the most active person involved in the pirate radio movement. He can be found doing interviews in contemporary articles and magazines, he often held broadcasts with similar radio stations, he wrote many widely distributed books on pirate radio, and he even helped radio stations get started by providing technical assistance. His book This is Free Radio (こ れ が 自由 ラジ オ だ), basically a manual on how to start a pirate radio station, was widely read and is referenced as an inspiration for multiple stations.

Similar “talk-show” like stations existed; two of note are Setagaya Mama and Komedia Suginami, as they are often found in the same magazines as Radio Home Run. The first station was held within an alternative retail store. The retail store would sell “everyday items”, such as door frames, windows, wooden chairs, and even wooden horses. The building is described as having a “window within a window that opened twice”, and it was often used as a place to try and develop self-sufficiency among its customers. They would sell materials to build things like doors and would give “instruction booklets” in plastic bags alongside them.

The station was made as a “broadcast for the elderly” (all of those involved in Setagaya Mama were elderly) and was made to be a talk show about whatever the guests wanted. The customers in the store could participate whenever they wanted, and the Suigyu Gakudan article on the first day they aired even talks about having sounds like door slamming as an integral part of the show. There were some interesting ideas to have the store itself reflected in the broadcast, such as hanging equipment from the ceiling.

The other station, Komedia Suginami, was started by Togo Igawa, a now famous London voice actor and a then ex-participant of the left-wing Zenkyoto movement. It ran inside a coffee shop called “Poem” (there is no information on this coffee shop itself) and had a similar logic to Setagaya Mama. The customers of the coffee shop could participate in the show, and sources state a wide range of people came from activists, businessmen, and the homeless, and that they talked about subjects such as relationship advice, local politics, a recent funeral, and so on.

Komedia Suginami held multiple broadcasts on the 1985 police raid of the radio station KYFM (discussed below) with other radio stations. This might be a good time to bring up the practice known as “ragchew (ラグチュ)”, where radio stations would set up their equipment in such a way that multiple stations could be heard at once. This would allow for real-time conversation between stations, and through the use of send-in letters and phone calls, involved the listener as well. These conversations deeply interested listeners, and one station even reports having continuous calls from 11 PM to 3 AM. The ragchew was one of the main practices that garnered interest in mini-FM and kept it well into the late 80s.

1985

Of course, with the rise in popularity, the demands for radio transmission increased and came squarely into conflict with the Radio Regulations Law. This is precisely what led to the 1985 police raid of the mini-FM station KYFM. It was a station held inside a rental studio that played late-night jazz and rock music. KYFM had apparently set up five locations, and one magazine reported that some of the disc jockeys would come to the station drunk.

They had gained much popularity over the past year, often being criticized for attempting to be a “big radio station”, and on September 5th, 1985, they were subject to a police raid, fined for broadcasting waves exceeding the legal limits, and the owner of the rental studio was arrested (according to Tetsuo Kogawa, one Asahi Shimbun reporter told the station they would be raided the next day though they could not divulge any further information).

This event was met with shock for a variety of reasons. For one thing, the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, the Japanese body responsible for enforcing communications laws, tracked KYFM for months without giving any notice. For another, there was, as a matter of fact, no way to reliably measure the strength of radio waves at the time. The equipment to do so is expensive, and there were very few people with advanced technical knowledge in the mini-FM scene.

From the Ministry’s perspective, this only made matters worse because it would mean that, most likely, the majority of “mini-FM” stations were, in fact, illegal. Many stations were relaying their signal at different locations, and there are a few instances of DJs saying things like “even if I had to weaken the signal, I wouldn’t know how”. Given that there was no way to measure it and that the limit for the signal strength was “extremely weak” by definition, it would stand to reason that it would be easy to accidentally surpass the limit.

From the perspective of the radio pirates, this was a form of government suppression. They saw the police raid as “setting an example”, and multiple newspaper interviews have the radio hosts expressing concerns that there would be a general crackdown among all mini-FM stations. Furthermore, the secrecy on the part of the Ministry, the lack of any warning (which was standard practice for breaches like this), and instead the direct arrest, only led fuel to this suspicion. Perhaps they were right, as one NHK official stated, as documented in a 1985 Asahi Journal article, in direct response to a slogan that had become popular at the time, “The radio waves do not belong to the people”.

There was much discussion around this event; there is no shortage of newspapers and radio shows discussing the incident. Some argued that the laws themselves should be changed and advocated for resistance against this, as was done in places like France and Italy. Others argued that the radio stations exceeding legal limits were “disrespectful” to the ones that maintained themselves within the Radio Regulations Law. Though there was much discussion around this, it seems that no general “crackdown” occurred, and the radio stations more or less functioned normally.

The Fall of Mini-Fm

Mini-FM did not last forever. It seems that it started to decline in the late 80s and fell off completely around the 90s. The reasons for this are varied: First, mini-FM in Japan was replaced by a new movement,“Community FM”; in 1988, Japan revised some of the Radio Regulations, making it easier to gain a license for broadcasting. This led to licensed stations that had a similar community focus. These stations often focused on local news and emergency broadcasts; they were, in fact, essential to the response to the 1995 Kobe Earthquake, which itself led to a further rise in Community FM stations.

Second, one could say that the “mini-FM” stations fell under their own weight. Given their small nature, only a few people were involved, and even fewer were radio hosts or DJs. So, when the original hosts moved on, there was no one left to replace them, and the station was abandoned. Of course, any pirate radio station that would expand would no longer be mini-FM (and also would have to deal with the police), so this problem occurred by design.

Last, and maybe most important, mini-FM died out because radio as a technology died out. Starting in the late 1980s, new forms of technology such as the cell phone and the MP3 player came to replace the function of radio as it was used by the public. There was no longer much of a reason to use radio to find music, gather news, or communicate with each other, as was done with CB Radio (the type of radio used in walkie-talkies). The internet provided text and visual communication, things that radio could only provide in a tangential form (through verification cards, letters, etc.).

The rise of MP3 downloads, YouTube, torrenting, and the like also allowed for greater accessibility to music. The user of this technology became more active than they generally were when using the radio (one must search for a specific song when using an MP3 player; in the case of radio, the song is chosen by the host). It seems that radio died simply because the public preferred other forms of technology.

Today, this contrast is only more apparent. The internet has expanded to a massive degree and has become a necessity of everyday life. Video communication, especially after the pandemic, is a preferred method, and the connection between phones and computers is more reliable, fast, effective, and consistent than it would ever be on a public radio. The rise of podcasts also throws into question the relevance of radio if one wants a form of audio-only communication. Still, pirate radio and mini-FM in particular is interesting insofar as it is a form of using media in a creative way.

Though new technologies have risen, their creative use has stagnated (similar to how one sees massive amounts of experimentation in early film though today the standard film is a Blockbuster movie). One can only imagine how these new technologies could be used in a similar fashion.

Tracing how jazz evolved from Lupin’s charm to Bebop’s sci-fi western universe.