Laputa: Castle In The Sky - Hayao Miyazaki’s Ode To Animation

Laputa│© Studio Ghibli

Before Totoro, before Spirited Away, there was Laputa: Castle in the Sky, a film that cemented Hayao Miyazaki’s vision of what animation could be. A floating fortress in the clouds, a world where machines still served people (not the other way around), and an adventure built on childlike wonder. But Laputa was almost never made. Before sky pirates and giant robots, Miyazaki had a very different project in mind. This is the story of how Laputa became the foundation of Ghibli, the dream that almost slipped away, and the ideals Miyazaki still fights for today.

Background

By 1985, Hayao Miyazaki had successfully reached his ultimate goal - creating his own animation studio. After the success of Nausicaä which, to the surprise of most people, was released under Topcraft Studio, Miyazaki along with Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki founded Studio Ghibli on June 15, 1985. Takahata and Miyazaki were already good acquaintances as they had worked together on movies such as “The Great Adventure of Horus” and “Panda Kopanda”.

Suzuki, who worked as an editor, might seem unimportant to the creation of Studio Ghibli, but his role should not be undermined. Without him, Miyazaki would never have become as popular and Ghibli would not have been created. Not only did he help popularize the manga of Nausicaä, but also served as the producer for films released under Studio Ghibli, which was an important role as theatrical releases of anime were expensive and often complicated to pitch.

On August 2, 1986 “Tenkuu no Shiro Rapyuta” i.e. “Laputa: Castle In The Sky” was released in Japanese theaters, Studio Ghibli’s first official movie. Unknown to most is the fact that Laputa almost ended up never being created. Before coming up with the idea for the movie, Miyazaki originally planned to create a movie about the water pollution of canals in Yanagawa (Fukuoka) called “Blue Mountains”, which was later released under the name “The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals” in 1987. The reason for the delay was the immense cost of making the movie. Since Miyazaki was financing it from his own expenses, Isao Takahata proposed that Miyazaki should direct a second movie to help with finances and so Laputa was born.

Laputa imageboard│© Studio Ghibli

The Idea Behind Laputa

The idea for Laputa was born in elementary school and expanded upon when Miyazaki visited Wales in 1985 on a research trip to get ideas for his new movie. Once known, the references to Wales become clear. Ranging from the old stone castles to the mining town Pazu grows up in, it is almost an exact copy of the old mining towns that Wales was famous for.

On his trip, Miyazaki witnessed the 1984–1985 United Kingdom miners' strike, which would become a leading motive throughout the movie. In 1985, coal mine workers started protesting against the closure of coal pits that had been nationalized by the British government and were deemed as uneconomic. For him, the death of the mining industry was an attack against the working class by the government that had failed to keep production going.

In Laputa, the working class, although depicted as ruffians that aren’t exactly smart, are helpful people that protect young Pazu from the pirates and government, although they are not involved in the conflict. In the original plans of the movie Miyazaki outlines the setting of the working class:

“Peace reigns in the bountiful land; farmers take joy in their harvests, craftsmen take pride in their works, and merchants take good care of the goods they sell, there is no conflict between the townspeople and the farmers, and a gentle equilibrium reigns. There are some poor people, but they help each other. Sometimes the harvests are rich, sometimes there are droughts and famines. It is a world where bad people coexist with good people.”

It becomes clear that the world of Laputa is a representation of Miyazaki’s longing for simpler times. Times when technology was still only used for machines that humans ruled and not the other way around. Where people took pride in their work instead of having to work jobs they do not enjoy (which has become a problem in Japan as surveys show that they no longer feel that their jobs give them any purpose).

Contrary to Nausicaä, which was aimed at an older, more mature audience, Laputa was made for a younger audience. Laputa, originally just called “Pazu”, was intended to be a refreshing take on a typical adventure story that could make you laugh and at the same time convey an honest message. Miyazaki knew that after the success of his latest movie, mature audiences would watch the movie regardless of the fact that it was aimed at young children, so he was able to focus his energy on making the film enjoyable for a younger audience without having to cater to the needs of adults.

For him, animation had always belonged to children: “In the midst of this, it is important for us not to lose sight of the fact that animation should above all belong to children, and that truly honest works for children will also succeed with adults. Pazu is a project to bring animation back to its roots.”

Laputa│© Studio Ghibli

Themes

A motive that would become typical for Miyazaki was the evolution of technology and the subsequent destruction of nature. Movies like “Princess Mononoke” have become cult classics for their critique of technological progress and even though Laputa is aimed at a less mature audience, it does not shy away from showing the destruction that humans unleash upon nature.

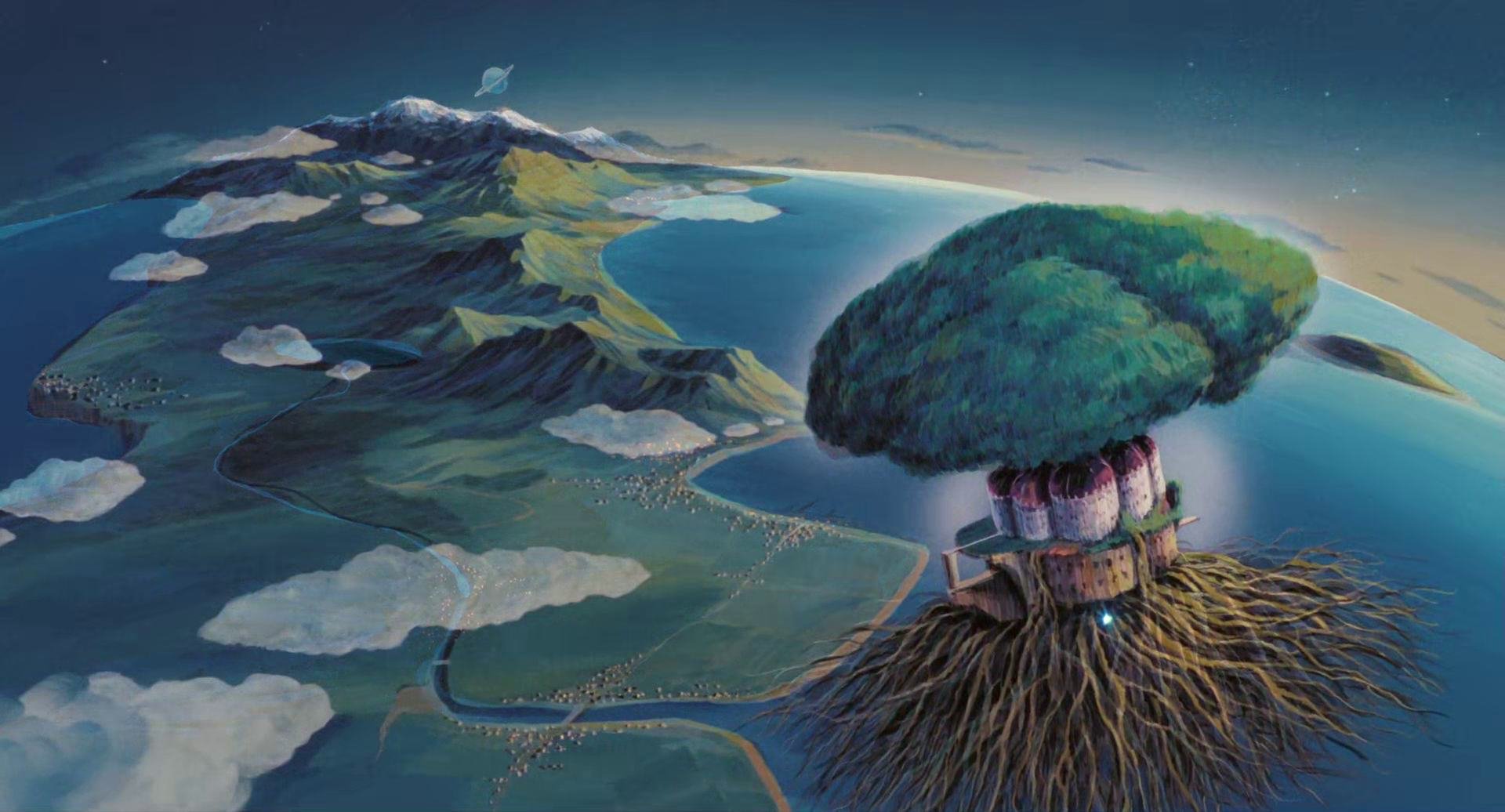

In Laputa, Miyazaki envisions an ecological utopia, a world where humans live together peacefully with nature. This utopia is represented by Laputa itself. The flying castle is built around a giant tree, symbolizing how nature intertwines the lives of the inhabitants and although the castle features technology, such as the iconic iron robots, its purpose is to protect nature and not destroy it.

The robots are quite important in signaling this message as they only harm humans when they attempt to exploit nature. Pazu and Sheeta misinterpret the robot’s actions at first when they arrive at Laputa thinking it is going to destroy their kite, although it only wanted to protect the nest of a flycatcher. Violence is only used as a response to the violence inflicted by others - “No matter how many weapons you have, no matter how great your technology might be, the world cannot live without love.”

In the original notes for Laputa, Miyazaki says that the story is set in a time when humans are still enjoyable and technological progress does not scare people like it does nowadays. He is not completely opposed to technology but prefers the olden times when it was only used for certain jobs and had not become a staple in all of our lives. The working class has become dependent on heavy machinery for many of their jobs and Miyazaki knows and respects this.

The ending of the movie, which shows the destruction of Laputa after Pazu casts the spell of destruction, is Miyazaki’s final message to us that it might be possible to coexist with nature, although there’s still a long way to go. While the city is destroyed, the tree ascends into the sky, becoming unreachable for Pazu and Sheeta. It is a symbol of our failings and, at the same time, a message of hope that even if it looks unreachable, we should strive to protect nature and coexist with it instead of destroying it for our egotistical needs.

Flycatcher nest│© Studio Ghibli

Inside the legacy of one of anime’s most iconic studios.