SUKEBAN - Japan's 70s Delinquent Girl Gangs

Tokyo, mid-1960s. A newspaper headline warns of trouble. Not for student protests, pollution crisis or rising crime rates. Instead, it introduces a new phenomenon to Japanese society, one driven by rebellion and led by the most badass girls in Japan, the Sukeban.

We take a look at the circumstances which created the environment for the Sukeban to emerge, thrive, and leave a lasting impact on society.

In this article

Japan’s increase of juvenile crime

The rise of school groups

The Sukeban emerge

Sukeban fashion

The rules & violence of the Sukeban

How media was influenced by Sukeban

The remains of the Sukeban

Japan’s increase of juvenile crime

Japan is known today as an organized and extremely respectful society. With its deeply ingrained collectivist mindset, immaculate clean streets, and a social hierarchy founded on integrity, the country inspires and attracts people from all over the world, inviting them to experience its unparalleled hospitality firsthand.

Yet even a society as neatly organized as Japan isn’t immune to juvenile crime. In the years after World War 2, the reported incidents of juvenile crimes nearly tripled compared to the pre-war era.

The atmosphere for challenged youth performing a different range of crimes was being enforced by the presence of American troops all over Japan, combined with immense poverty and sad living conditions while the defeated country was being reconstructed. As the 1950s came closer, these juveniles were being labeled as troublesome post-war youth.

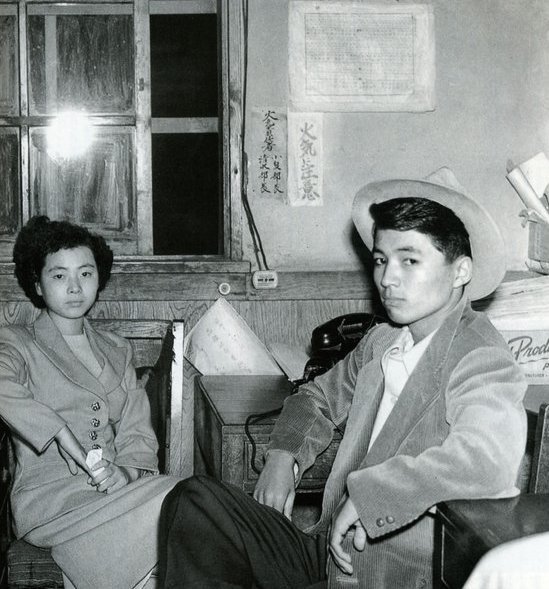

One event stands out for its profound impact on public perception of these young criminals, the 'Oh, Mistake' incident. On September 22nd 1950, a truck was heading towards Tokyo University. It’s cargo? Nearly 2 million yen in wages for university workers, money that would never reach its destination had it not been for 19-year old Yamagiwa Hiroyuki. As the truck approached, Yamagiwa, who was a university worker himself, signaled it to pull over.

As the truck came to a full stop, Yamagiwa took out a knife, jumped into the vehicle and slashed the neck of one of the three men inside. He then shoved the men out of the truck and took off. Two days later the police tracked down Yamagiwa and his girlfriend, with which he went on a crazy spending spree. Upon his arrest, Yamagiwa tried to make the officers believe it was a mistake, claiming he was a Japanese-American by yelling in crappy English ‘O, Misuteiku!’, which gave the crime its iconic name.

The ‘Oh, Mistake’ incident became the prime example of ‘after-war’ crime under US occupation, and the massive media attention it received made clear to the public that juvenile delinquency is at an all-time high. As the rise in juvenile crime incidents kept increasing during the 1950s, a climate conducive to more serious offenses beyond mere schoolyard bullying and petty crimes began to take shape.

Yamagiwa Hiroyuki and his girlfriend

The rise of school groups

With juvenile crime at an all-time high, we have to look at the schoolyard as the breeding ground for these young offenders. Bullying and stealing lunch money is nothing new among students worldwide. However, in Japanese schools, a phenomenon occurred that distinguished typical bully behavior from the initial stages of an organized crime organization.

In the unstable Japan of the 1950s, junior high, spanning from ages 12 to 16 in Japan, provided the perfect setting for young, rebellious minds—often from working-class backgrounds—to break any chains that were holding them back. The most remarkable and “strong” student delinquents would gather other students around them.

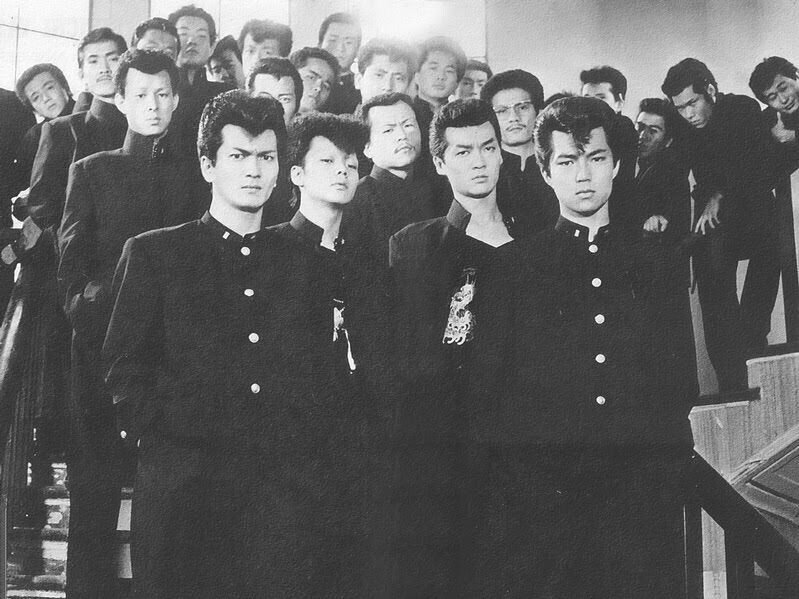

The idea of a small group of troublemakers looking up to a leader quickly grew into something more serious when the groups started identifying as actual groups, implementing a hierarchy. These groups became known as Bancho.

Bancho were male-exclusive group of young delinquents, with a Bancho as their leader and up to five lieutenants per group. The total number of group members would range anywhere between 20 and 60. Looking up to the Yakuza, Bancho were meticulously organized, establishing internal hierarchies and conducting annual selections. These selections involved planning fights, with the winner ascending to the role of Bancho for the following year.

The violence and crimes of Bancho group were relatively harmless and went from intimidation and theft, to beating up non-members and even teachers. Remember, we’re still talking about young boys here, many of whom would continue to join a Bosozoku biker group or even become a organized syndicate member.

The heydays of the Bancho were between the 1950s and 1970s, until a new group of young delinquents emerged that would continue their legacy.

Bancho group

The Sukeban emerge

With the Bancho dominating the school grounds and strictly limited to male members, there was no room for girls to make their stand. If anything, the Bancho reinforced the idea of Japan being a male-dominated society in the eyes of these young girls. Thus, driven by a revolutionary mindset and new ideals of freedom, feminism, and the desire for self-expression, Sukeban was born.

The Sukeban were composed entirely of female members. (Sukeban combines "su" meaning girl and "bancho" meaning thief. Editor's note.) These Japanese delinquent girl school groups would outnumber their male counterparts.

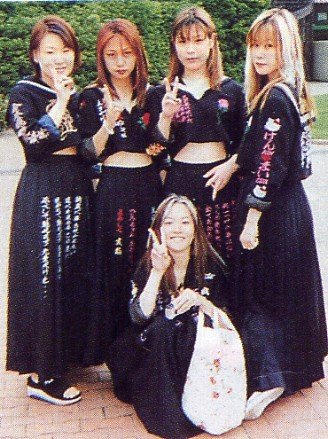

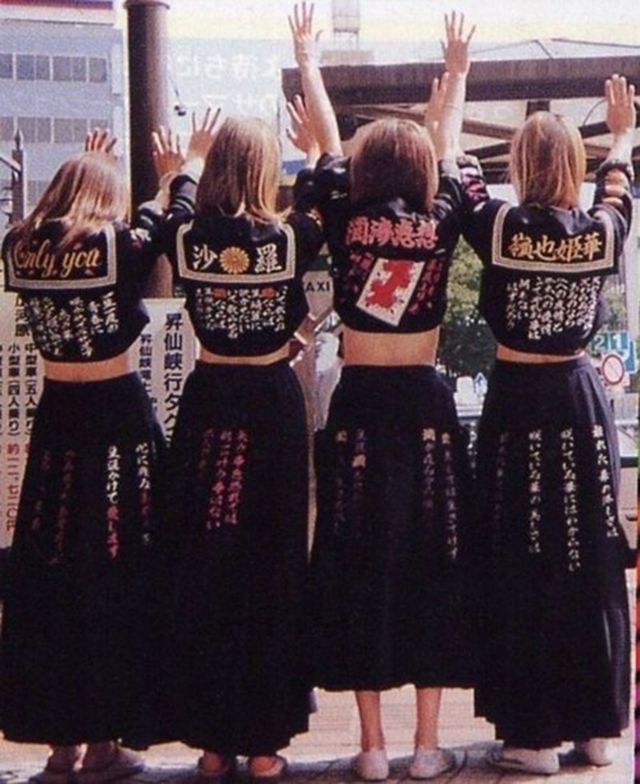

Forget the images that have shaped your stereotypical depiction of Japanese schoolgirls since the mid-1990s. No more portrayals of sweet-eyed innocent girls in short school skirts, victimized by a macho society. Picture instead a Yakuza-style female hierarchy with its own rules and rituals. They ditched the short skirts, opting for longer ones in protest against being objectified. Comfortable Converse sneakers replaced classic moccasins, while their outfits featured punk and anarchist influences.

Sukeban girls

Members were often from lower class families. These girls were confronted with the fact that their heritage brought limitations as they viewed life through a different perspective. They had no hopes of becoming career women with a top floor office.

The Sukeban defied gender norms and patriarchal expectations, and aimed to leave their mark on a male-dominated society by refusing to conform to authority. Just the concept of a woman behaving “independently” or “badly”, was enough to shake Japanese society and, for the Sukeban, was an exciting experiment to challenge the constraints of the society they found themselves in.

If we take a look at the Yakuza reigns, we see an organization with no place for women. Despite the rare presence of female yakuza members, they had zero authority through the eyes of male Yakuza members and were only granted informal roles. This in itself indicates the shock factor the rise of a female-exclusive group must have brought. Even with its members being young girls, they boldly ventured into uncharted territory within Japanese society. Perhaps it's this audacity that solidified the Sukeban's place in history, as both rebels and cultural icons.

Sukeban fashion

A significant aspect of the Sukeban's rebellion was expressed through their fashion choices. Rejecting the conventional, they challenged the restrictions and expectations of traditional school uniforms which featured short skirts, often viewed as oppressive and sexist.

To both make a stand and distinguish themselves from regular students, the girl group members altered their skirts, making them way longer. The long skirts in addition to adding kanji and other writing on their uniform became the iconic symbol of Sukeban culture during the 1970s.

Other than these alterations, the Sukeban outfit remained a ‘normal’ school uniform, but the girls wearing it were definitely not following the ‘normal’ behavior their school and society had in mind. Also, the outfits carried much more than rebellious flair, as often hidden under those long skirts were cutters, chains, and razor blades.

The Rules and Violence of the Sukeban

In essence, just like the Bancho groups, Sukeban is made up of youngsters. While they may bear a resemblance to the kingpins of Japan’s organized crime syndicate, their activities primarily involve minor offenses.

Nonetheless, the Sukeban weren’t to be messed with. The groups engaged in theft, vandalism, and violence. The subculture thrived on being badass and disrespectful, turning it into a real national concern echoed across Japan.

Inside each group, there was a strict set of rules and hierarchy. With rules like “don’t use drugs” or “don’t have relationships with other group member’s partners”, loyalty was essential. Breaking it or disrespecting a superior could lead to severe consequences like being burned with cigarette butts.

To those unfortunate enough to fall victim to a Sukeban group, they seemed like violent girls without ethics or a moral code. Let’s say you didn’t want to find out what was hiding underneath that skirt.

Yuki Saito in Sukeban Deka│© Toei

How media was influenced by Sukeban

The Sukeban had a major influence on media , especially in entertainment. Their rebellious flair led to a film genre called Pinky Violence. Known for its violence and eroticism featuring Sukebans or school girls, Pinky violence became an extremely popular genre during the 1970s. Manga, books, anime, and even adult content showcased the rebellious girls from groups.

Pinky violence was all about female violence aimed at entertaining an adult audience. Toei, Japan’s media giant, even made it into a separate category. The genre absolutely dominated the Japanese entertainment industry in the 1970s and 80s. Even Sailor Moon creator Naoko Takeuchi stated to be inspired by the Sukeban.

Here are some examples of media heavily influenced by or based on Sukeban culture:

Movie: Girl Boss Guerilla (1972)

Movie: Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion (1972)

Movie: Lynch Law Classroom (1973)

Manga: Sukeban Deka (1975)

Movie series: Sukeban Deka (1987)

Game: Sukeban Deka III (1988)

Scene from Lynch Law Classroom

But even beyond the borders of Japan, the Sukeban left their mark. Have a look at the young Japanese high school student Gogo Yubari in Kill Bill. Three guesses where Tarantino found the inspiration.

The inclusion of violent women in films, manga, and anime, drastically changed the portrayal of women and femininity in Japan during the 1970s and 1980s. The Sukeban grew from a local school group to a nationwide phenomenon, leaving its mark on society.

Despite the media frenzy, the Sukeban were still active, instilling fear in Japanese students who would grow terrified by the idea of being confronted by a Sukeban member. At the same time the media attention would introduce middle-class women to a new genre, one where young independent women were being portrayed in a way they never experienced before.

In the end, it was all about introducing the idea of women being able to be straight up bad-ass. Although the motive likely leaned more towards profit than societal impact, the media that was published based on Sukeban culture changed Japan’s views on women, the ability to resist, and make a stand for your beliefs.

The remains of the Sukeban

Today, juvenile crime in Japan is in steep decline. While there are groups of young criminals who wreak havoc in their free time, their impact and organizational structure doesn’t come close to that of Sukeban groups during the 1960, 70s, and 80s.

Over time, the Sukeban phenomenon, while still carrying the ideals of freedom and revolution, began to fade. Perhaps the massive media exposure that slowly transformed it into pop culture may have contributed to its decline. Originally created to shock and challenge society, the Sukeban culture eventually succumbed to its own charm and boldness, leading to its downfall. The rebellious and violent image of the groups, from sneaky school bathroom smoking to theft and street violence, was softened for mass entertainment.

Today, the romantic side of it all remains. A new generation of girls found its own means of making their stand. Through eccentric fashion, social media, and community they find a form of rebellion. The violent and brutal sides of the Sukeban phenomenon are overlooked to highlight the small but significant role it played for Japanese women and perhaps even women worldwide.

Discover Sukeban's evolution from gritty films to iconic anime figures.