Tokyo Turntables - The Japanese-American Hip-Hop Exchange

East End x Yuri - denim-ed souL cover

The thundering beats, spit-fire bars, hair-raising dance moves, and striking graffiti bombs of hip-hop culture have garnered worldwide adoration and adoption. However, Japan's embrace of hip-hop goes beyond mere admiration; the very essence of hip-hop has been intertwined with Japanese heritage from its inception.

Hip-hop culture awakened in the rhythm-pumped streets of the Bronx in the 1970s. In the desolation of the economic collapse, restless youths turned to electric self-expression, spraying graffiti on crumbling walls, breakdancing on discarded cardboard, and brightening dreary hardships through vibrant musicality.

The genre's emergence is credited to hip-hop’s founding holy trinity: Afrika Bambaataa, DJ Kool Herc, and Grandmaster Flash. The iconic trio is responsible for legitimizing the emerging cultural revelation and defining its four original elements: DJing, rapping (MCing), breakdancing (breaking or b-boying), and graffiti.

While hip-hop began as a local phenomenon, the intermingling of Japanese music and hip-hop goes back to the birth of hip-hop itself. In fact, hip-hop founding father Afrika Bambaataa himself credits Japanese musicians for the genre’s existence: namely, the wildly influential Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Prophets of Hip Hop - Yellow Magic Orchestra

Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) was a Tokyo-based electronic music band formed in 1978, comprised of Haruomi Hosono, Yukihiro Takahashi, and Ryuichi Sakamoto. The band’s innovative style produced a profound, broad, and lasting global cultural impact.

Proof of YMO’s genius is evident through the extensive collection of covers, samples, and collaborations they’ve inspired. Michael Jackson, Mariah Carey, J Dilla, and even Arca (who met Ryuichi Sakamoto at a Björk concert, of all places) are prime examples of artists within YMO’s star-studded sphere of influence.

One of YMO’s earliest and most significant contributions to hip-hop comes from their 1978 debut single Firecracker, released in the United States under the title Computer Games. The song was a massive hit in the burgeoning hip-hop community, becoming a key source of inspiration for the genre's consequent development. YMO even performed the hit single live on Soul Train — validating and immortalizing their impact on hip hop. Afrika Bambaataa himself sampled the song during a live DJ set in the Bronx, and cited YMO’s videogame-funk style as an inspiration for the song Planet Rock.

Early Pioneers of Japanese Hip-Hop - Toshio Nakanishi and Hiroshi Fujiwara

At the turn of the 80s, hip-hop’s electrifying rise began to gather more international attention. Global creatives traveled to New York City and Philadelphia just to get a taste of the viral sensation. Among these creatives were Japanese artists Toshio Nakanishi and Hiroshi Fujiwara, whose immersive experiences in the bustling NYC hip-hop scene would profoundly shape the trajectory of Japanese urban culture.

Toshio Nakanishi, frontman of Japanese New Wave bands The Plastics and Melon, came to New York as an acclaimed star with international tastes. The purpose of his fateful 1981 trip was to perform as an opener for Talking Heads in Central Park. At the time, Afrika Bambaataa’s YMO-inspired hit, Planet Rock, was booming across the city, beckoning Nakanishi to experience the live performance himself. At the Bambaataa show, Nakanishi was stunned by the display of fresh hip-hop music and hypnotic breakdance, punctuated by electrifying record scratches.

The impactful performance inspired Toshio Nakanishi to incorporate record scratches on his Tokyo DJ sets and introduce breakdance to Japan. He hired the very same breakdancers he witnessed to perform in two (unfortunately abandoned) music videos for his band, Melon: Don’t Worry About After Death and Final News. While Nakanishi’s eccentric new influences didn’t immediately resonate with Japanese audiences, the seeds of NYC hip-hop culture had been planted in Japan.

Another primary witness of thriving New York City hip-hop culture was the ultra-influential Hiroshi Fujiwara, the godfather of streetwear and Ura-Harajuku, credited with developing Japanese hip-hop and shaping Japanese urban culture. Fujiwara was also a young creative infected by the hip-hop bug. He traveled to New York City in the early 1980s and brought back golden nuggets of hip-hop culture in the form of a record collection. Taking on the role of a Japanese hip-hop messenger, Fujiwara began to integrate these records into his club DJ sets and write about the genre in Japanese news columns. He also formed his own hip-hop group, Tiny Panx (タイニー・パンクス).

A young Hiroshi Fujiwara

The influence of hip-hop would go on to deeply permeate Fujiwara’s future creative endeavors in streetwear fashion, too. Hip-hop and punk were critical elements of the fashion guru’s artistic visions, setting the Ura-Harajuku scene for fashion designers like Nigo (Tomoaki Nagao), the founder of A Bathing Ape (or BAPE). The hip-hop cultural feedback loop between Japan and America has been intensely active for decades, feeding countless iconic moments in hip-hop history. Just to scratch the surface: Pharrell Williams’ partnership with Nigo and the consequent Billionaire Boys Club label, Nicki Minaj’s Harajuku Barbie persona, and Ye’s Dropout Bear Bapestas. Kid Cudi even worked at the New York City BAPE store before his music career took off.

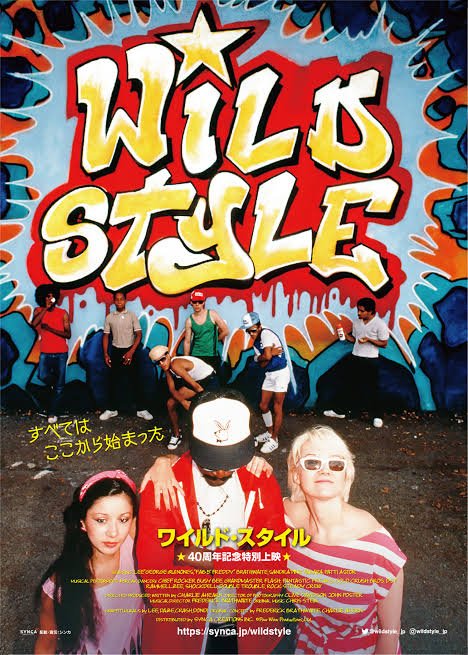

Hip-Hop’s Official Japanese Debut - Wild Style

By 1983, hip-hop had undoubtedly reached Japan — but it was far generally unpopular and only understood by a niche audience. However, this year, a major cultural turning point would occur: the premiere of the first-ever hip-hop film, Wild Style.

Despite its New York City setting and roots, the first hip-hop film didn’t premiere in the Big Apple — it premiered in Shinjuku, Tokyo. DJ Yutaka, an early Japanese hip-hop DJ and a member of Afrika Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation, hosted the Wild Style crew during their tour. The result of Wild Style’s Tokyo showing? A musical revelation that spread like wildfire across Japan. Hip-hop’s new presence on the big screen gave the Japanese audience a comprehensive overview of hip-hop culture. All four original elements of hip-hop (graffiti, breakdance, deejaying, and rap) were represented within the film, much to the intrigue of Japanese viewers.

The cultural impact of Wild Style in Japan was instant and massive. Hip-hop simply clicked. Suddenly, the overlooked kindlings of hip-hop culture in Japan were ignited into a blazing pandemonium that spread like wildfire.

Perhaps the most instant outcome of Wild Style’s showing was the start of the renowned DJ Krush’s career. When DJ Krush, or simply Hideaki Ishi at the time, attended Wild Style’s premiere, he changed his life right then and there. The former yakuza underling purchased turntables the day he watched the film and began his DJ career. DJ Krush became a pioneer of Japanese hip-hop and gained international acclaim for his work — all thanks to Wild Style.

Cover of Wild Style│© Submarine Entertainment

Success stories like that of DJ Krush rely not just on inspired individuals but also on interested audiences. The Japanese public's growing respect for hip-hop opened the floodgates for a new outpour of culture. The works of pre-Wild Style artists like Toshio Nakanishi and Hiroshi Fujiwara finally established a stable foothold in Japan. Record scratching and rapping were no longer strange one-off phenomena to the Japanese public; they were elements of hip-hop. In 1986, the first hip-hop club, fittingly named Hip-Hop, opened in Tokyo, furthering the genre's reach.

Over the decades, hip-hop continued to gain traction in Japan. Hip-hop groups like Scha Dara Parr, Rhymester, and Buddha Brand emerged in the late 80s and early 90s, achieving astounding success across Japan. Popular tracks include Scha Dara Parr and Kenji Ozawa’s 1994 smooth sensation Konya wa Boogie Back (今夜はブギー・バック) and EAST END + YURI’s 1994 lively pop-rap track DA.YO.NE — the first non-English Japanese hip-hop song to sell a million records. Tracks like these legitimized Japanese hip-hop as a serious genre; not a foreign fad. Hip-hop’s hold on Japan was there to stay.

Japan’s Breakdance Craze

The full embrace of hip-hop's musical elements in Japan was a gradual process, but one element swiftly permeated Japanese culture: breakdance, or b-boying. As a part of Wild Style’s promotion in Japan, pioneer breakdancing group Rock Steady Crew (RSC) showcased their prowess across several Tokyo venues, from department stores to clubs. RSC's gravity-defying moves instantly captivated Japanese audiences, underscoring the universal language of dance.

Breakdance's rapid resonance in Japan may also be linked to a significant but little-known Eastern influence ingrained in this hip-hop element. Rock Steady Crew president Crazy Legs directly attributes his crew’s ultracool moves to the striking maneuvers of East Asian martial arts. “The only place I’d say we learned moves from, which was universal for a lot of dancers, was karate flicks on Forty-Second street,” Crazy Legs explained, “‘cause those movies are filmed the best, you could see the movement of the whole body” (Fernando 1994, 18). In some ways, breakdancing’s arrival in Japan may have felt more like a homecoming than a foreign import.

Within a month following Wild Style’s premiere, Yoyogi Park — a cultural hub in Harajuku — was already abuzz with the rhythm of breakdancers. Among the earliest breakdancing groups to pop up around Harajuku were B-5 Crew, Mystic Movers, and Tokyo B-Boys. Phenomenal floorwork, stunning acrobatics, and an edgy flair made breakdance groups crowd favorites.

One of the most notable early breakdancers and the first official B-boy in Japan is Crazy-A, leader of the Tokyo B-Boys. The dancer was personally requested by Crazy Legs of RSC himself to lead a brand new Japanese chapter of the famous Rock Steady Crew. Crazy-A’s devotion to hip-hop made him a linchpin of the Japanese breakdance scene.

In 1999, 16 years after Wild Style, Crazy-A founded B-Boy Park (1999-2017), an annual two-day hip-hop festival bursting with cultural value. Deemed Japan’s biggest block party, the festival celebrated hip-hop culture with bumping music and intense dance competitions in Japan’s breakdance mecca, Yoyogi Park. Breakdance’s astounding impact on Japan continues to reverberate; explosive fits of breakdance are celebrated alongside the orderly queues and polite bows of Japanese culture.

Japanese Arcade - A Hip-Hop Haven

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Japan’s vibrant arcade scene morphed into a hip-hop haven. Over the years, all four original elements of hip-hop have found a home in the heart of arcade culture.

One arcade game forever associated with Japanese culture is Dance Dance Revolution, where players step on lit-up arrows in a rhythmic sequence to perform a dance. Breakdancing aficionados take the game a step (and a headspin) forward with their own sub-genre of the game known as DDR (Dance Dance Revolution) Freestyling. The in-game points of a technically perfect performance are traded for an immense expression of creativity, often watched — and sometimes judged — by a large crowd. Binary platform sequences take a backseat as the dancers perform original breakdances.

Record scratching at the arcade became possible in 1997 with the introduction of the Beatmania series in Japan. In the game, you are a DJ competing for the audience's praise. With the help of a keyboard and turntable, Beatmania turns the arcade into your own personal nightclub. While the DJ gameplay is far from the real deal, its hip-hop roots are undeniable.

Even rap made its way to Japan’s arcade scene, in the most kawaii way possible. The 1996 rhythm game PaRappa the Rapper received critical acclaim and a cult following for its inventive gameplay and endearing protagonist. Players follow PaRappa, the paper-thin rapping dog, dripped out in a beanie, baggy jeans, and skate shoes. The game is a series of rap battles, ranked on a scale from “Awful” to “Cool” on the “You Rappin’” meter. True to the origins of hip-hop, freestyling is encouraged — and it may give you the edge you need to achieve top scores in the notoriously challenging game. PaRappa has garnered several accolades and has even been featured as the main character of his own 30-episode anime series.

This list would not be complete without the inclusion of Street Fighter: a distinguished arcade game that has honored and contributed toward hip-hop culture. Street Fighter debuted in 1987, drawing inspiration from a fragment of the unfinished 1978 Hong Kong martial arts film Game of Death, starring Bruce Lee and NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Hip-hop influence punches you in the face as soon as you boot up the game — literally. The game’s opening sequence depicts a character smashing through a brick wall covered in graffiti (one of hip-hop’s four original elements). This depiction of graffiti is a digitally preserved testament to graffiti’s presence in Japan despite its relatively muted existence.

Graffiti, arguably the most controversial element of hip-hop, faces considerable challenges given Japan’s strict cultural aversions to public defacement and vandalism. Although full-blown spray-painted graffiti has dared to decorate Japan on several occasions, graffiti tags are often quickly scrubbed away. Even major designated graffiti spots like the Yokohama Wall of Fame (Sukuragicho Station Wall) have been literally grayed out. The 1987 game’s inclusion of graffiti in its opening sequence and fight backgrounds immortalizes this underrepresented hip-hop element’s impact on Japan.

Street Fighter also made waves in the rap industry. The game’s most obvious link to rap culture emerged with the release of Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike in 1999. Canadian Rapper Infinite turns the Street Fighter character selection into a lyrical odyssey with his featured rap, Let’s Get It On, set to a James Brown sample.

VERSE - “Yo, I know ya got your options / So pick the right thing Some choices to make / And mad ruckus to bring”

Infinite’s Street Fighter rap heralded the beginning of a robust cultural exchange between hip-hop and the Street Fighter franchise. The influence of hip-hop in the game grew from a whisper to a roar with Street Fighter III’s A Tribe Called Quest-inspired soundtrack. Street Fighter’s iconic imagery has led to countless game references within the realm of rap. Notable references have been featured in the raps of artists like Lupe Fiasco, Drake, Nicki Minaj, Snoop Dogg, 50 Cent, Lil Wayne, Wyclef Jean, Meek Mill, Kevin Gates, M.I.A, and Chief Keef, to name just a few.

Recently, hip-hop’s influence has made an incredible resurgence within the Street Fighter franchise with the 2023 release of Street Fighter 6 — 36 years after the game’s original debut. Breakdancing, DJing, rapping, and graffiti are heavily represented in the game’s newest installment with extreme intentionality. Street Fighter exemplifies the enduring and innovative relationship between Japan and hip-hop culture, a synergy that continues to evolve and thrive today.

Nujabes' Impact on Anime’s most Iconic Soundtrack.