Yohji Yamamoto - The Poet of Black and Avant-Garde Fashion

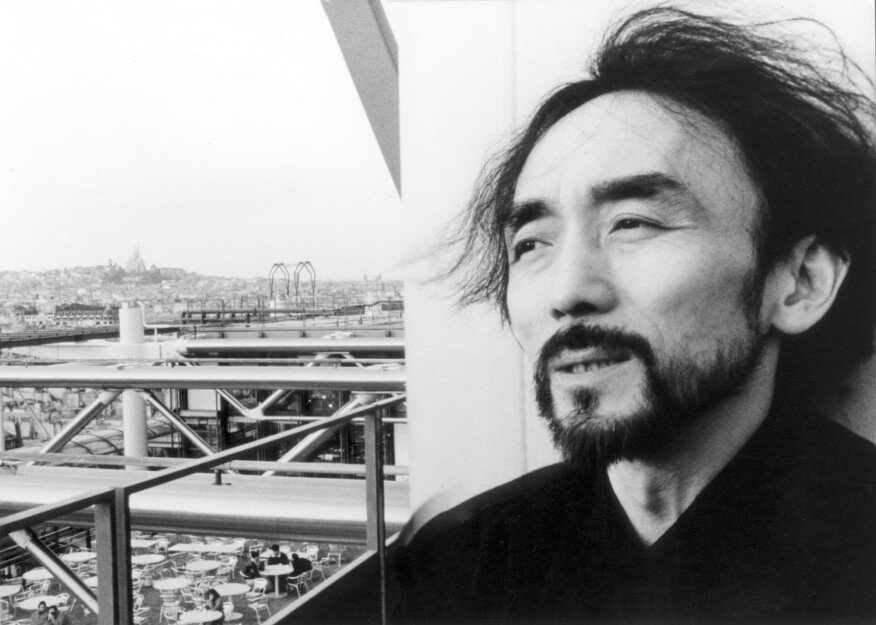

Yohji Yamamoto in 2010│via Wikimedia Commons│© Masaki H.

Few figures in the fashion world embody the essence of rebellion and reverence as perfectly as Yohji Yamamoto. A designer who crafts philosophies woven in black, Yamamoto has become synonymous with avant-garde fashion, Japanese artistry, and a defiance of convention. To understand Yohji Yamamoto is to walk a line between darkness and light, between diligent craft and radical abstraction. Spotting a Yamamoto piece will never not feel like encountering a statement, an enigma.

Growing up

Yohji Yamamoto was born on October 3, 1943, in Tokyo, just as the world was changing irreversibly. Post-war Japan was a canvas marked by devastation, but also resilience that led to Japan’s avant-garde renaissance —a contrast that would come to define much of Yamamoto’s work. His father died in the war, leaving him and his mother to forge a path on their own. His mother ran a dressmaking shop in Shinjuku, a neighborhood already buzzing with life and ambition. It was in that shop, surrounded by fabric and the mechanical hum of sewing machines, that Yamamoto’s love for fashion was first sparked.

In interviews, he has recounted his childhood as a time when he simply “wanted to do nothing.” But those moments were steeped in observation—watching his mother’s hands move with precision, turning raw fabric into garments that would soon clothe the neighborhood’s women. Here, Yamamoto learned two things that would stick with him for life: the value of craftsmanship and the silent strength of women.

By the time Yamamoto was old enough to choose a career, Japan was knee-deep in a Westernization wave that prized corporate, stable professions. It was no surprise then that he enrolled in Keio University to study law, completing his degree in 1966. Yet, as fate would have it, a career in law wasn’t in the cards. “I didn’t want to enter regular society,” Yamamoto has said, a simple phrase that underscores the restlessness that would define his path. Instead, he returned to his mother’s dress shop, learning the technical aspects of tailoring and garment construction. At her request, he enrolled at Bunka Fashion College, one of Japan’s most prestigious fashion schools, which had only recently begun admitting male students.

Yohji yamamoto in Notebook on Cities and Clothes│© Wim Wenders Foundation

The Early Collections

In 1972, Yamamoto launched his first label, Y’s, a name that would grow to hold the same weight as Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake. Y’s wasn’t about ostentatious fashion statements; it was about a new way of dressing. His collections were a radical departure from what was considered fashionable at the time. While the Western world was fixated on glam, form-fitting clothes that showcased every curve, Yamamoto was crafting oversized, draped garments that veiled rather than revealed. He aimed to guard, not expose, the female form, offering women a kind of sartorial sanctuary.

The Japanese market was initially hesitant, conditioned as it was to prefer Western and hyper-feminine styles. But for those who were open to seeing fashion as a form of silent rebellion, Y’s became a manifesto.

By 1981, Yamamoto felt ready to take his philosophy to the global stage. His Paris debut coincided with that of Rei Kawakubo, a moment that would shake the core of the fashion establishment. The collection, which featured oversized, torn garments, drew immediate controversy. The press reacted with confusion and, in many cases, scorn. Influential trade publications published critiques that bordered on vitriolic, marking photographs of the show with crosses to signify rejection. The term Hiroshima chic emerged, casting Yamamoto’s work as bleak, almost accusatory.

For Yamamoto, this response was disheartening, but despite the harsh reception, a select group of people saw the significance of his collection. They saw that Yamamoto’s pieces weren’t just anti-fashion; they were a new form of fashion, an unorthodox response to the polished, sometimes superficial nature of Western style.

The garments were unsettling in their defiance. The models wore flat shoes, their hair unstyled, and their makeup minimal—an intentional push against the glamour and perfectionism that defined the fashion scene. This raw, unpolished presentation drew the ire of many but also the fascination of those who were ready for something real, something that spoke to the spirit rather than just the body.

The Runways That Shaped his Legacy

Fall/Winter 1983 - The Black Collection

In the 1983 Fall/Winter collection, Yohji Yamamoto solidified his reputation as a disruptor in the fashion world. The show’s emphasis on black served as a fundamental medium for showcasing structure and form. Yamamoto utilized asymmetric hemlines, unconventional draping, and a layering technique that defied traditional Western tailoring. This collection was groundbreaking as it highlighted the philosophy of “Ma”—a Japanese concept of negative space—shifting global fashion discourse towards minimalism. Critics at the time, including those from The New York Times and Vogue, noted the show’s influence on a generation of designers who began to reexamine the artistic and functional roles of color and silhouette in their work.

Spring/Summer 1998 - A New Romanticism

Spring/Summer 1998 was a notable departure from Yamamoto’s traditionally austere aesthetics, embracing a softer, romantic direction. Flowing silks, chiffon, and tulle were utilized to craft garments that retained his avant-garde ethos while introducing fluidity and movement. This collection’s signature look involved dresses that exuded an ethereal quality, layered with sheer materials and delicate embroidery.

Fall/Winter 2000 - Arctic Inspiration

The Fall/Winter 2000 collection was notable for its conceptual alignment with themes of survival and resilience, inspired by the harshness of Arctic climates. The runway featured models in voluminous, cocoon-like coats, layered knitwear, and oversized fur-lined boots. This collection stood out for seamlessly merging utilitarian fashion with a high-art aesthetic.

Fall/Winter 2024 - Reflecting on Legacy

The Fall/Winter 2024 show was a heartfelt retrospective imbued with Yamamoto’s signature touch of melancholia and innovation. Drawing from archival motifs, he revisited some of his most iconic themes, such as voluminous silhouettes and brushstroke graphics, but reinterpreted them with contemporary elements. Notable pieces included baggy trousers painted with abstract art and coats adorned with pinup illustrations, echoing his playful yet profound exploration of past influences. The decision to include models of different ages, including director and friend Wim Wenders, and actor Norman Reedus, was a nod to his inclusive vision of beauty and a statement on timelessness in fashion.

Signature Design Philosophy

“Black is modest and arrogant at the same time. Black is lazy and easy—but mysterious.” This quote from Yamamoto is iconic, and it speaks volumes about how he views the cornerstone of his work. Black, in his hands, is more than a color; it’s an attitude, an assertion that one doesn’t need to shout to be heard. His garments in black are studies in contrasts: sharp but soft, heavy yet fluid. Walking through Tokyo, it’s not uncommon to see figures clad head-to-toe in Yamamoto’s pieces, their silhouettes cutting through the landscape like shadows.

Yamamoto’s approach to asymmetry is another facet that sets him apart. Unlike traditional Western tailoring, which often prizes symmetry as an ideal, Yamamoto finds beauty in the unexpected, the imperfect. This inclination is deeply rooted in the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, the idea that there is beauty in imperfection and impermanence. His clothes are often asymmetrical, with folds, drapes, and unexpected seams that play with the viewer’s eye and challenge conventional ideas of balance.

A New Vision of Feminism in Fashion

One of Yamamoto’s most profound contributions is his vision of feminism in fashion. Unlike many designers who leaned into the male gaze with their work, Yamamoto’s designs have always aimed to empower women by de-emphasizing the traditional markers of femininity. He once remarked, “I wanted to protect women’s bodies from something—from men’s eyes, or a cold wind.” His coats, dresses, and trousers were made not to highlight but to shield, offering an unspoken solidarity to women who wore them.

Long before gender fluidity became a widely accepted concept, Yamamoto was already blurring the lines. His collections often featured garments that transcended traditional gender boundaries, allowing individuals to express themselves without conforming to societal expectations. This approach resonated deeply in Japan and abroad, changing the conversation around what it means for clothing to be ‘sexy.’ Instead of exposure, Yamamoto championed mystery. Yamamoto’s work has influenced a wide range of styles, from streetwear to high fashion, encouraging a more inclusive and fluid understanding of clothing and identity.

Yamamoto’s Ventures that Changed the Game

Y-3 - The Birth of High-Fashion Sportswear

In 2002, Yohji Yamamoto and Adidas embarked on a groundbreaking collaboration that led to the launch of Y-3 in 2003. This partnership blended Yamamoto’s avant-garde design philosophy with Adidas’ sportswear expertise, giving birth to a new genre that would be recognized as athleisure. Yamamoto’s vision was to make sportswear elegant and chic, a concept that was ahead of its time.

The inaugural Y-3 collection debuted at Paris Fashion Week in October 2002. Besides merging high fashion and sportswear, the collaboration created a whole segment in the market. Yamamoto himself expressed that Y-3 opened a new niche in the fashion and sportswear market. One of the most iconic creations from this collaboration is the Y-3 Qasa High sneaker, introduced in 2013. Its design, featuring a neoprene sock-like upper and an expressive EVA outsole, set a new standard in sneaker aesthetics. The Qasa High’s influence became apparent in many contemporary sneaker designs that followed.

In no time, Y-3 became deeply interwoven in Tokyo’s subcultural scene. The brand launched the Style Guide series on Youtube, inviting influential figures like Utaha from Wednesday Campanella to assemble their favourite Y-3 fit. Over the years, Y-3 has continued to innovate, introducing collections that push the boundaries of fashion and sportswear. In 2022, as part of their 20th-anniversary celebrations, Y-3 even reintroduced the iconic Qasa High.

Ground Y

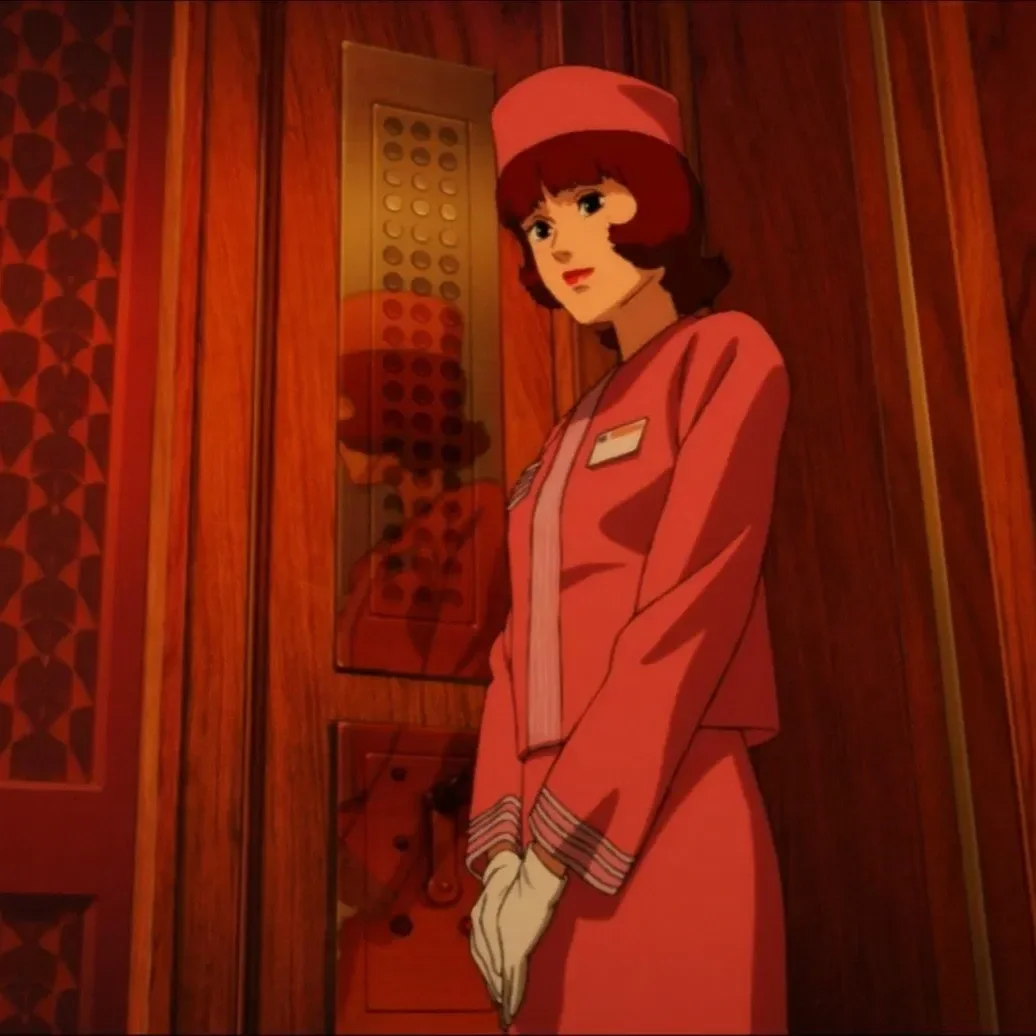

Ground Y is Yamamoto’s sub-label which stands as a manifesto of genderless and ageless style. The label is also known for its dynamic collaborations, which blend fashion with various cultural influences. Notable partnerships include collaborations with iconic franchises such as Cyborg 009 and Evangelion, as well as with contemporary artists like Keiichi Tanaami.

Ground Y x Evangelion collaboration│© Yohji Yamamoto

Art & Cinema

Yamamoto’s influence isn’t limited to the fashion runway; he has also ventured into art, music, and film. Yamamoto’s foray into cinema is marked by his collaboration with acclaimed Japanese director Takeshi Kitano, as he designed the costumes for Kitano’s 2000 film Brother. Further exploring the intersection of fashion and film, Yamamoto was the subject of Wim Wenders’ 1989 documentary Notebook on Cities and Clothes. This film delves into Yamamoto’s creative process and his reflections on the relationship between fashion, identity, and urban life.

In the art world, Yamamoto has engaged in collaborations that blend visual art with fashion. His partnership with the art director duo M/M (Paris) in the late 1990s resulted in a series of avant-garde catalogues and campaigns. These works featured surreal imagery and innovative typography.

Yamamoto’s influence even extends to the realm of manga, where he collaborated with manga artist Junji Ito, integrating Ito’s distinctive horror aesthetics into fashion pieces. This fusion highlights Yamamoto’s ability to bridge diverse cultural expressions, creating garments that resonate with both fashion enthusiasts and manga fans.

Junji Ito x Yohji Yamamoto collaboration│© Yohji Yamamoto

A Designer Who Walks the Dark Side

Yamamoto has often described himself as a designer who operates “in the dark,” and this isn’t just metaphorical. He has always preferred to stay on the fringes of mainstream fashion, operating outside its glitz and overindulgence. This focus on the fundamentals of garment-making has kept him grounded and respected, even as fashion itself has morphed into a spectacle.

Despite his global success, Yamamoto has never had an interest in the business side of fashion. This ambivalence led to challenges, most notably in 2009 when his company faced financial difficulties and filed for bankruptcy. A private equity firm stepped in to save the day, but Yamamoto’s commitment to creativity over commerce was laid bare. When asked about it later, he admitted that he would have ended his career had it not been for his daughter, who convinced him to continue.

Yohji Yamamoto transcends the boundaries of a mere designer; he’s a movement, a mindset. His legacy lies not only in the clothes he’s made but in the boundaries he’s pushed and the ideas he’s seeded in the minds of those who wear his creations. His work challenges us to rethink what fashion can be—a canvas for expression, a shield for the soul, and a declaration of independence from the mundane.

Even now, in his eighties, Yamamoto shows no signs of slowing down. Each collection, whether it embraces color or adheres to his signature black, comes with an underlying message: stay true to your voice, even if it whispers in the dark.

Japan’s konbini culture is evolving, and NIGO is leading it.