Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s Happy Victims - Fashion Shrines in Tiny Spaces

Jane Marple│© Kyoichi Tsuzuki

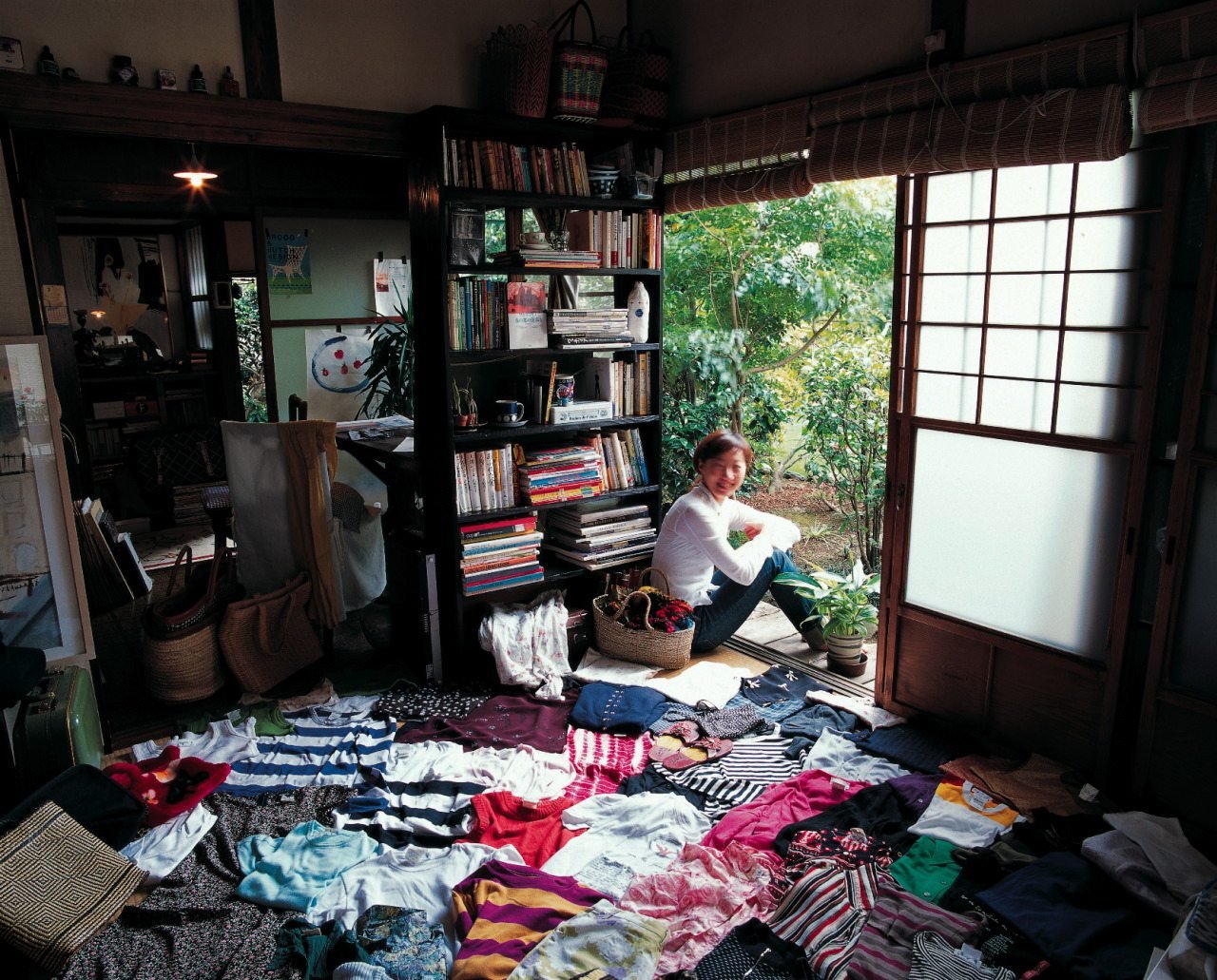

What if every square inch of your tiny Tokyo apartment bows to the altar of a single designer. Margiela in the kitchen. Chanel on the windowsill. Helmut Lang perched awkwardly on your only chair. What if the line between devotion and obsession for your favourite designer starts to blur? Thanks to Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s Happy Victims series we know exactly what this would look like.

Between 1999 and 2004, Tsuzuki stepped into the private sanctuaries of 30 self-proclaimed “fashion victims” across Tokyo. These weren’t glamorous fashionistas on magazine covers, but everyday people, living in cramped spaces, utterly consumed by their love for high-end brands. Their apartments became living archives of Alexander McQueen gowns, Undercover jackets, and Vivienne Westwood corsets—a chaotic juxtaposition of high fashion and low square footage.

But why “victims”? Tsuzuki doesn’t use the term lightly. These collectors—some might say hoarders—have sacrificed much for their obsessions. Financial strain? Certainly. Space to breathe? Absolutely. Yet, as the title suggests, their suffering is tinged with joy. They’re victims of their passions but revel in their “happy” martyrdom, surrounded by the objects of their desire.

The Art of Organized Chaos

What makes Happy Victims so compelling is its honesty. Forget glossy fashion editorials where models lounging in luxury. Tsuzuki turns that idealized narrative on its head. His subjects live in spaces that, at first glance, seem mismatched with the luxury they covet. Kitchens double as closets. Beds are buried under piles of designer clothes. Sometimes, there’s not even room for the collector in the shot—just a sea of meticulously arranged couture.

Each photograph is an invitation to linger. Tsuzuki’s lens is intimate but never voyeuristic, blending empathy with a touch of humor. You can almost feel the Helmut Lang devotee’s minimalist philosophy echoing in their Spartan room. Or the playful rebellion in a Vivienne Westwood fan’s cluttered, punk-infused apartment. In these portraits, the designers’ identities bleed into the collectors’ personalities—a symbiotic relationship where the clothes wear the people just as much as the reverse.

Consumerism or Identity?

Tsuzuki doesn’t spoon-feed you answers. His work leaves you grappling with questions about consumer culture and personal identity. Are these individuals simply trapped in a materialistic cycle? Or is their devotion a creative expression of self in a society where space and individuality are at a premium?

The accompanying texts offer glimpses into the logic—or madness—behind the collections. One collector explains how their wardrobe feels like a piece of armor, protecting them from the outside world. Another confesses that their life revolves around saving for that next Prada coat. These stories transform the photos from static portraits into living, breathing testimonies of modern desire.

A Legacy That Endures

When Happy Victims was published in 2008, the luxury fashion world reacted with unexpected discomfort. Tsuzuki had exposed the underbelly of high fashion: the people who buy the clothes but don’t fit the aspirational image sold by glossy ads. Yet, over a decade later, the series continues to resonate. In the age of social media, where curated closets are flaunted for likes, Happy Victims feels oddly prescient. It forces us to ask: Is our love for brands any less obsessive today?

For Tsuzuki, this project wasn’t just about fashion—it was about humanity. The “victims” in his photographs might seem extreme, but they reflect a universal truth: we all find meaning in the things we love, even if they consume us. In their tiny, overstuffed rooms, they find joy, purpose, and identity. And maybe, just maybe, that makes their so-called victimhood something to envy.

Turning the calming Japanese bathhouse into a creative playground.