Love and Pop - Hideaki Anno’s Experimental Portrait of 90s Japanese Youth

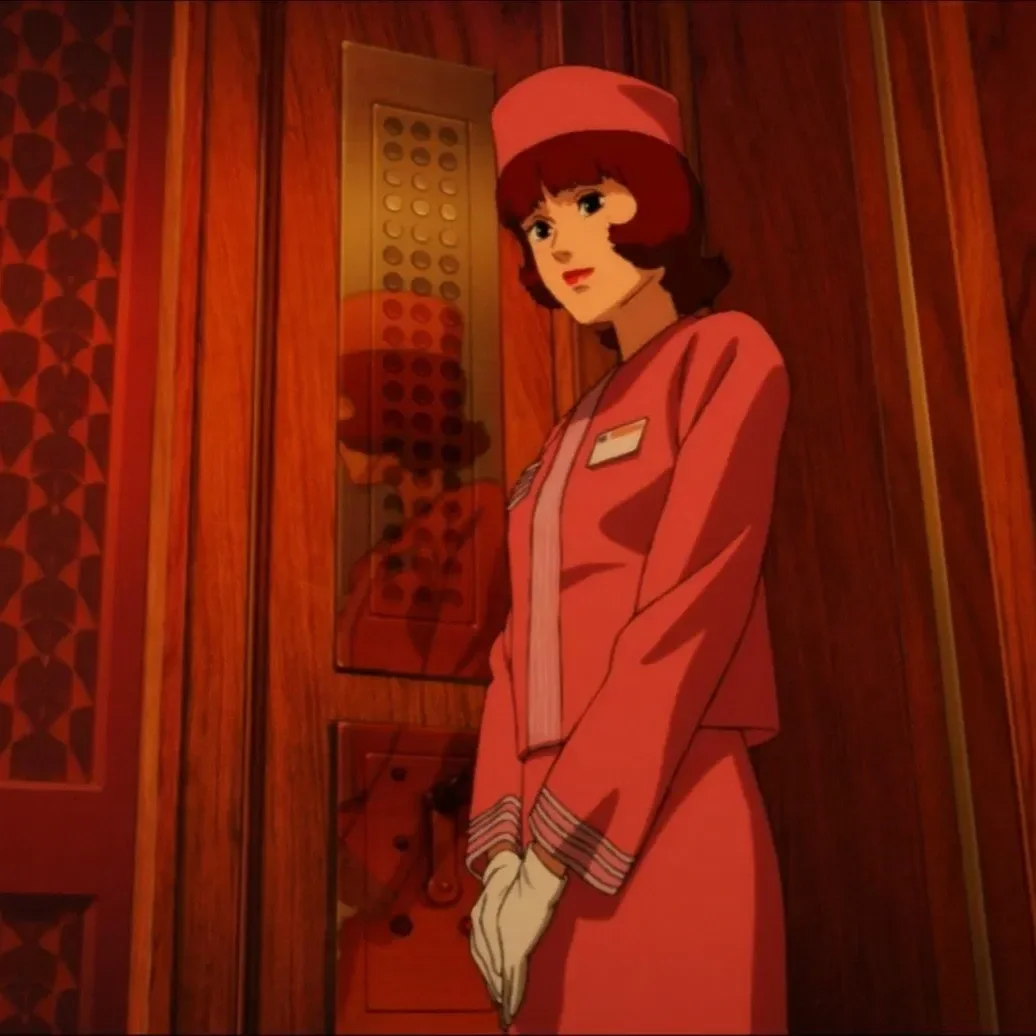

Still from Love & Pop│© Toei

After revolutionizing anime with Neon Genesis Evangelion, Hideaki Anno turned to live-action cinema with Love & Pop (1998). Through an experimental digital style, Anno explores the fragile world of a high school girl caught on paid dates with older men, capturing the disillusionment, consumerism, and identity crisis of Japanese youth in a society adrift.

In 1995, Hideaki Anno revolutionized Japanese animation with Neon Genesis Evangelion. The filmmaker is then exhausted by the experience following the considerable work that was accomplished after 26 episodes and two feature films. On the Internet, Anno discovers that he is being threatened with death by fans unhappy with the conclusion of the series. Demotivated, depressed, he decided to escape from the world of animation for a while, and ventured into live-action cinema for the first time with Love & Pop. Adapted from the novel Topaz II by Ryu Murakami, this film offers a disturbing insight into the daily life of a Japanese high school student. Attracted by the promise of a futile object, she lets herself be drawn into the opaque universe of enjo kousai, these priced meetings between young girls and older men, a phenomenon that hit the headlines in Japan in the 90s.

The director chooses a unique approach, both sensory and experimental. He captures the fragility of his heroine through a radical staging device, shooting with a digital camera on the shoulder. The film multiplies extreme angles, unusual focal lengths and subjective shots, transforming each scene into an immersive experience where the character's confusion is reflected in the very form of the story. This visual bias, combined with fragmented editing and an elliptical narration, gives Love & Pop a unique identity, at the crossroads of documentary cinema and psychological essay.

Beyond its formal audacity, the film paints a disturbing portrait of Japanese youth in the 90s, torn between economic insecurity and the quest for sensations. It questions the relationship with the body and money in a society where human connections are monetized. Even more, it is a continuation of the themes dear to Anno: solitude, social pressure and identity wandering, already at the heart of Evangelion, and which still resonate today in his cinema.

Japan In The 90s - Between Disillusionment And Consumerism

Love & Pop is part of a rapidly changing Japan, marked by the after-effects of the bursting of the economic bubble in the early 90s. After decades of dazzling growth, the country is going through a prolonged recession, giving way to a climate of uncertainty and precariousness which particularly affects young people. Promises of a bright future are crumbling in the face of an increasingly competitive job market and social pressure that weighs heavily on individuals, particularly students. In this context, some Japanese youth are developing a complex relationship with money and human relationships. Consumerism becomes a refuge and a means of self-affirmation, while new forms of transactions emerge, blurring the lines between desire and necessity.

It is in this atmosphere that the phenomenon of enjo kousai, literally “compensated relationships”, where high school girls agree to paid dates with older men. While some of these exchanges are limited to conversations and outings, others involve sexual relations, making this phenomenon as taboo as it is widespread. In Japanese media in the 90s, enjo kousai is widely publicized, often under a sensationalist prism which reduces these young girls to figures of depravity or victims of consumer society. With Love & Pop, Anno takes the opposite of this approach by offering a subjective and immersive dive into the daily life of a high school student confronted with these dilemmas, without ever falling into Manichaeism.

Love & Pop cover│© Toei

The story follows Hiromi, an ordinary high school student who shares her carefree daily life with her friends, oscillating between idle chatter, dreams for the future and more down-to-earth concerns. One day, she comes across a ring in the window, a piece of jewelry that she ardently desires but cannot afford. Her desire to acquire this object gradually becomes an obsession, pushing her to consider a quick way to earn money. It was then that she came into contact with an informal network of enjo kousai, where men offer her money in exchange for a simple date. What begins as a game, tinged with excitement and carefreeness, quickly turns into a disturbing experience. Hiromi finds herself confronted with men with ambiguous intentions, oscillating between benevolence, condescension and barely veiled hostility. The more she gets involved in these encounters, the blurrier the line between control and loss of self becomes.

Beyond the simple story of an adolescent drift, the film dwells on the complexity of human interactions, refusing to judge or moralize. Thus, by setting his plot in a Japan in crisis and by adopting an approach that is both intimate and immersive, Hideaki Anno captures not only the instability of a generation in search of bearings, but also the weight of a society where the need to exist sometimes involves transactions where bodies and emotions become commodities.

A Radical Aesthetic

If Love & Pop strikes with the accuracy of its gaze, it is above all through its singular cinematographic language that it manages to translate the psychological state of its heroine. By borrowing from both the codes of documentary and advertising, the film captures the raw energy of everyday life while conveying the inner confusion of its character.

Unlike traditional cinema productions shot on film, Love & Pop is entirely filmed with DV (Digital Video) cameras, a choice still rare in 1998. This technology gives the film a grainy texture and an almost amateurish appearance, reinforcing its anchoring in reality. But Anno pushes the experimentation even further by adopting an almost omniscient approach to the camera. Throughout the film, she seems gifted with absolute freedom, sneaking from improbable angles, observing Hiromi from the bottom of a glass, the inside of a telephone receiver or even from an extreme dive at ground level. This instability of the frame evokes a fragmented gaze, as if reality itself were fragmented and elusive.

Beyond the frame, it is in its editing that Love & Pop displays all its radicality. The film multiplies brutal cuts, sudden accelerations and juxtapositions of discordant images. On several occasions, Anno inserts almost subliminal inserts (images of advertisements, light panels, telephone screens) which parasitize the story and reflect the visual aggression of contemporary urban Japan. Like the bold and experimental montage of Evangelion, Anno masters the filmic language to deliver a unique, deconstructed, unpredictable and confusing work.

Love & Pop is part of a tradition of Japanese cinema exploring youth and its malaise (as is Shunji Iwai's 2001 film All About Lily Chou-Chou), and is distinguished by a resolutely avant-garde visual approach. The film seems to anticipate trends that we will find in digital cinema of the 2000s, where DV will become a privileged tool for capturing immediacy and intimacy (L'Enfant by the Dardenne brothers, Ken Park by Larry Clark). This experimental style, although it may have been disconcerting upon its release, is fully in line with the creative logic of Anno, who will continue to explore these techniques in his subsequent works. We thus find a similar approach in Shin Godzilla (2016) or in the latest Evangelion films, where the omnipresent camera captures the action from unusual angles, where the fragmentation of the story reaches its climax.

Cover of Animage featuring Hideaki Anno with Love & Pop stars Kirari, Yukie Nakama, Asumi Miwa and Hirono Kudo

A Critique Of Consumerism And Adolescent Malaise

The trigger for the plot is an innocuous object: a ring in the window which irresistibly attracts Hiromi. This jewel, which has no functional value, becomes a symbol of the desire to possess, of the need to materialize an ephemeral desire. Its price places it beyond the immediate reach of the high school student, and it is this inaccessibility that fuels her obsession.

This mechanics of desire is at the heart of consumerism. Indeed, it is not so much the intrinsic value of the object that matters, but the illusion it provides, the promise of fulfillment which, once the purchase is made, immediately vanishes. Hiromi does not seek to fill a fundamental lack, she simply wants to acquire something that seems beautiful to her, because the society in which she evolves has conditioned her to find meaning in possession. In this, Love & Pop illustrates how capitalism creates a permanent need for accumulation, where individuals do not pursue tangible happiness, but a succession of volatile aspirations. This desire for consumption is not unique to Hiromi: it is reflected in the behavior of her friends, who are obsessed with fashion, pop culture and current trends. The film thus shows how adolescent girls, despite their apparent independence, are in reality shaped by a society where everything, even their own image, becomes a commodity.

In this consumerist logic, the body also becomes an object of transaction. Enjo kousai, although being a socially taboo phenomenon, is part of a continuity where the relationship with money conditions human interactions. Young girls do not necessarily perceive these encounters as prostitution, but as a pragmatic way to respond to their immediate desires. Hiromi herself does not initially seem aware of the problematic nature of these exchanges. When she agrees to accompany men in exchange for money, it is not in a logic of survival, but in an almost playful approach, devoid of real seriousness. However, as the day goes by, this initial carefreeness crumbles, giving way to growing unease. Each interaction becomes a test of limits, a negotiation where power constantly oscillates between her and her male interlocutors. Some appear benevolent, others adopt a paternalistic stance or try to put pressure on it, illustrating how these power dynamics are ingrained in Japanese society.

Beyond the criticism of consumerism, Love & Pop highlights a deeper malaise: that of a youth in search of reference points in a society which offers them none. Hiromi and her friends spend their time chatting, laughing, wandering aimlessly. They do not seem overwhelmed by sadness, but an underlying emptiness emerges from their interactions. This wandering is not only geographical, it is also existential: they move forward without direction, lulled by the incessant flow of the city, in search of a passing excitement which would dissipate, if only for a moment, the monotony of their daily life. This feeling of alienation is reinforced by the way Japanese society is represented in the film, a world of screens, neon lights, constant noise, where human interactions are often superficial. Anno multiplies the shots where Hiromi is surrounded by anonymous faces, absorbed in their own concerns, thus emphasizing the generalized indifference that permeates urban Japan. This loneliness does not only concern the young girls, but also the men that Hiromi meets who seem lost, seeking to fill a void through these fleeting encounters. Some simply want to talk, others seek physical contact, but all seem to be searching for something indefinable. This need for human connection, made almost impossible by a society that values performance and emotional restraint, results in these monetized exchanges where everyone tries, in their own way, to fill a gap.

Where Love & Pop stands out in its refusal of moralism. Anno does not condemn Hiromi or the men she meets. He simply observes, leaving the viewer to draw their own conclusions. Rather than naming culprits, Anno highlights a system where individuals are caught in a spiral, conditioned by forces beyond them. Through Hiromi's journey, Anno invites us to reflect more broadly on the way in which capitalism and social changes transform our relationship with others and with ourselves.

Still from Love & Pop│© Toei

Anno’s Obsessions From Love & Pop To Shin Evangelion

Love & Pop is often perceived as a marginal work, but in reality turns out to be an essential link in the artistic evolution of the director. By freeing himself from the constraints of animation to explore the possibilities of cinema in live action, Anno refines a cinematographic language which will profoundly mark his later works, notably the Rebuild of Evangelion films (2007-2021) and Shin Evangelion (Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time). The movie is a laboratory where Anno tests narrative and visual processes that he will later reuse and perfect. Even more, the film prefigures certain themes and obsessions that will haunt his following films: the alienation of individuals in a hypermodern society, the quest for identity in the face of a world in decay, and above all, a reflection on the possibility of redemption through connection to others.

At first glance, the commonalities between Love & Pop and Evangelion might seem tenuous. However, in different forms, the two works address the same central question: how to grow up in a world that alienates us? Shinji Ikari, protagonist of Evangelion, is a traumatized teenager who oscillates between rejection and desire to belong, unable to understand what is expected of him. Hiromi, for her part, is not a tormented heroine in an apocalyptic world, but she shares with Shinji this same existential wavering, this difficulty in establishing a sincere link with her environment. Where Shinji flees reality by locking himself into a psychological withdrawal (hikikomori symbolic), Hiromi wanders in a society that dictates his value through his ability to seduce and consume.

In Shin Evangelion, this existential wandering reaches its climax. Like Hiromi, Shinji is a character caught in a cycle of repetition and doubt. But while Love & Pop ends with a disturbing ambiguity, Shin Evangelion offers a more assertive resolution: after years of wandering, Shinji finally manages to accept his humanity, breaking the cycle of suffering and repetition. One of the most memorable moments of the film is its finale, where the fictional world of the saga literally disintegrates to give way to a real shot, as if Anno was telling us that animation was only a prism, a mask through which he had always expressed himself. This idea of a transition to an adult world, where adolescent wandering gives way to self-affirmation, finds an echo in Hiromi's journey, although in a more diffuse form. From this point of view, Love & Pop appears retrospectively as a first outline of this questioning on the reconstruction of the self and the possibility of renewal.

So Love & Pop is not a simple curiosity in Hideaki Anno's career: it is a cornerstone, an essential work which announces the themes and formal experiments that the director will never cease to develop. By radically exploring the wandering and malaise of Japanese youth, by breaking the narrative and aesthetic codes of conventional cinema, Anno was already doing in 1998 what he would manage to sublimate more than twenty years later with the films Evangelion : a cinema which does not just tell a story, but which makes it felt in all its raw force.

Tokyo’s outsider spirit, Blue Spring, and emotion stitched into Elsewhere.