Shinjuku Boys - The World of Onabe

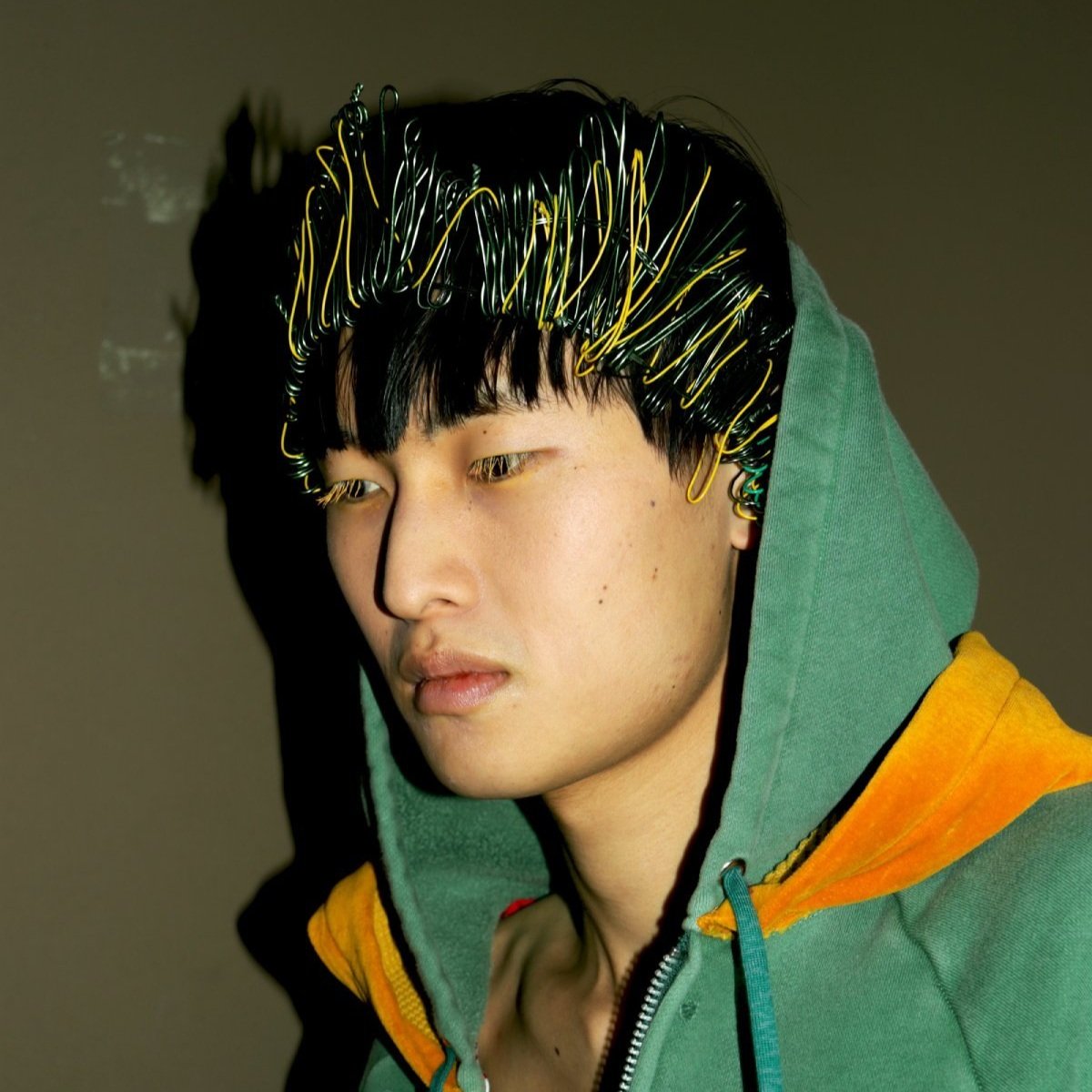

Still from Shinjuku Boys│© WMM

Onabe literally translates to “cooking pot”, but its social meaning hides an interesting reality about Japan’s LGBTQ+ community. Similar terms like dansousha, rezubian dansou no reijin, and & “MissDandy” became widely used in the media to characterize androgynous and/or sapphic women, especially in the entertainment industry, during the postwar era.

Initially widely used, now onabe doesn’t hold the same weight, but it is still of great importance to understand and dive into Japanese queer history.

The origins of onabe

Social non-conformity in a conservative and cis-heteronormative country like Japan can present difficulties, especially for women and anticonformists. Although with derogatory intent, new words to describe unconventionality came with the congruous facing of the rezubian spaces and groups in the 1960s and ūman ribu, the Japanese women’s liberation movement in the 1970s. There, onabe gained popularity in the media and was accepted as a distinct identity by people, particularly those employed in entertainment establishments like pubs and clubs.

Another common nickname for onabe in the media during the mid-1980s and early 1990s was “Miss Dandy”. This confused the terms rezubian and onabe, which refer to people who identify as non-female presenting, and have a sexual attraction to women, whether cis or transgender. Although not entirely replaced by onabe, the media used all cited terms interchangeably. To them, they could use any existing words to refer to lesbians, crossdressing bartenders, transgender individuals, and sapphic relationships.

Usually, onabe is used to indicate trans-masc individuals, although some, as shown in Shinjuku Boys, do not necessarily identify as trans, and sometimes do not mind female pronouns. Their views and situations are diverse, depicting gender fluidity and an unlabeled nature. Now less common, if not as a derogatory term, the word onabe is enriched with nuances and diversity.

Still from Shinjuku Boys│© WMM

Shinjuku Boys - a queer testimony

Back in the 90s, British directors Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams worked together on a documentary in the hope of a better understanding of said Japanese reality. The film follows the daily lives of Gaish, Tatsu, and Kazuki, three onabes working at the New Marilyn Club in Tokyo. At the center of the bustling and glitzy Shinjuku district, the nightclub offers their female customers handsome and charming masc-presenting AFABs (assigned female at birth) to keep them company with flirty conversations and champagne. The three protagonists, through alternating shots of them at home and on the job, converse and show the camera their daily lives and their personal views.

Tackling diverse social topics, the hosts open up about their romantic relationships and living their identity in a homophobic society. Gaish acts tough and flirts with many women, while Tatsu and Kazuki have stable relationships with their girlfriends. While doing so, they show lovey-dovey moments with their partners, heartfelt conversations, support of fellows onabes, and the coldness and confusion of their family. Although acting manly and being masc presenting, Gaish doesn’t start hormones, and they do not want to fall into a definite gender binary. Tatsu, instead, has started hormone treatments and is happy being considered a man. Lastly, Kazuki is in a happy relationship with another trans performer, who works at Pink Soda, a bar for those dressing or identifying as women. He, although, is not interested in consuming sexual acts, which probably anticipates an asexual discourse in Japanese media.

Such conversations show that the onabe world is diverse: they engage in relationships with both cis and trans women, they’re asexuals, or they experience the “couple life” as men in love with a female counterpart. It is difficult to define their identity because it’s not in line with a definite agenda: there’s limited knowledge about sex and gender and, also, there’s no need to, as nothing’s in black and white.

The conversations even cover society as a whole, tackling feminist and lesbian topics. For example, the customers of the New Marilyn have boyfriends outside the club, or they would like to have one, but they fear marriage and childbearing due to social pressure and misogynistic culture. Longinotto and Williams’ interviews of their protagonists are enlightening while depicting vulnerability, and reflecting the issues queer people might still face today in Japan. These are open and unfiltered portraits of individuals facing obstacles, covering sapphic lives, gender fluidity, and identity in contemporary Japan. Shinjuku Boys is one of many truthful depictions of Tokyo’s queer citizens.

Still from Shinjuku Boys│© WMM

Onabe today

As highlighted in Shinjuku Boys, onabe represents a complex relationship between gender identity, expression, and sexuality. They may identify as women, trans men, or just as onabe. With time, society changes, and newer and clearer testimonies surface. In today’s interviews discussing onabes, many openly identify as trans. People are more aware of hormones, surgeries, and the idea of ‘passing'“ as cis is not sought out by every trans person and shouldn’t be expected. Newer generations hold more knowledge, and, unsurprisingly, many consider onabe an offensive term. Today they might prefer the term FTM (female-to-male).

Marriage discussions also occur, as Tatsu and his girlfriend state they’d like to get married. Whether considered a same-sex relationship or one involving a transgender counterpart, rights to have LGBTQ+ marriages are still far from possible in Japan. Things may have changed, a little bit for the better, but the discourse shown is still relevant today.

Shinjuku Boys is a precious queer testimony that depicts diverse perspectives, without pushing one specific narrative on gender, sex, and identity. It gives space to an open discussion about social rights and expectations, which makes the documentary still relevant and contemporary despite being almost thirty years old. Concerning the film’s pivots, The New Marilyn Club is still alive and thriving, filled with straight women looking for comfort. It’s unclear where the protagonists are today, but this hidden and precious queer world is still researched by many.

Still from Shinjuku Boys│© WMM

The 70s schoolgirl gangs that shook Japanese society.